Elizabeth Gómez is a Redwood City based artist and children’s book illustrator. Part of Gómez’s practice involves designing and managing community participatory murals in both paint and mosaic.

I first met Elizabeth during her July 2021 Redwood City Art Kiosk exhibition. Her installation, Naturaleza Muerta, was striking in the manner it pulled the audience in and then held their attention with an edgy softness: A lifesize deer and mountain lion hang upside down in the center of the kiosk. They are accompanied by a squirrel and a crow. These hand sewn creatures are made from pale, low contrast fabrics. Scatterings of thin red cloth trail from each body. The kiosk floor is covered with pink quilting and a spare grid of deep red, fabric roses. There is a feeling of being in a child’s bedroom. These layers of symbolism reveal a multi-dimensional philosophy about the relationship of humans to other animals, to profound effect. In this work Gómez brings together a blend of Louise Bourgeois construction with Sue Coe content to make her own statement about real life events involving wild animals in our suburban neighborhoods.

Gómez has an MFA in Pictorial Art from San Jose State University. She has shown at the deYoung Museum in San Francisco; the Oakland Museum of California; MACLA in San Jose, California; and at the Mohr Gallery in Mountain View, California.

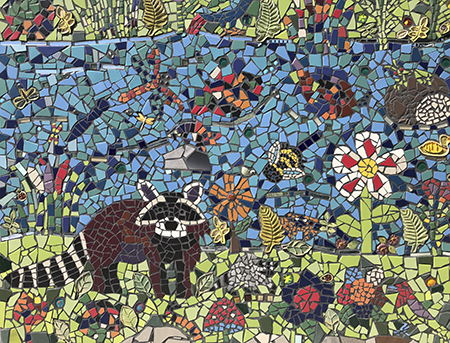

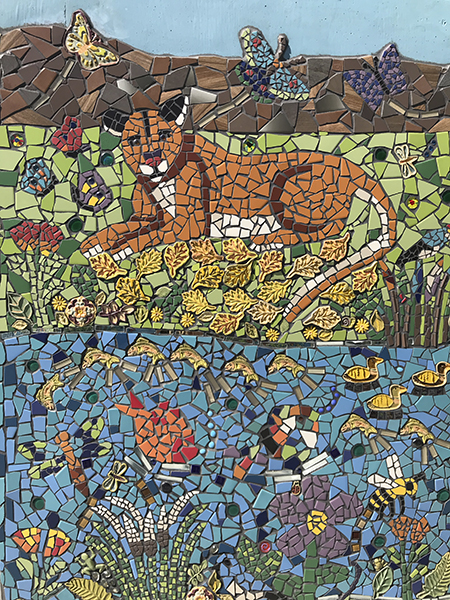

This week Gómez’s most recent mural, created with the help of many from our community, will be unveiled at the Magical Bridge Playground in Redwood City. We spoke during the last weeks of mosaic tile making under the redwoods and oaks on the back patio at Red Morton Park, the mural’s home.

Whirligig: Let’s talk about your background. You went to San José State?

Elizabeth: I did most of my college in Mexico City where I am from. I did three years at the San Francisco Art Institute and then I did my masters in painting at San Jose State. I had great professors like Erin Goodwin-Guerrero and Rupert Garcia. It was an excellent program, lots of support, really nice.

Whirligig: How long have you been working in mosaic?

Elizabeth: I have been doing small things here and there but I am really a painter. I have been working with Redwood City for many years. I have done murals in the schools and parks. The city knows me as an artist that can create and facilitate public works with volunteers, with the help of the community. That is why they asked me to do this mosaic mural. I have learned a lot doing this.

Whirligig: What are the dimensions?

Elizabeth: It is gigantic. It has more than 700 square feet of tile.

Whirligig: You did the design?

Elizabeth: I did the design and many workshops. For example, here in Red Morton Park during the pandemic we were outdoors and indoors and outdoors again and then we couldn’t do it at all. Then, I had to transport boxes of materials to the volunteers, house to house, I would bring a new box and take competed work away. I did that for many months. It was a lot of work. Then we were allowed to work here outside again, almost a year and a half after we started. The hardest thing about this project has been the management. We have had more than 750 volunteers on this mural. Everybody is welcome. I have taught the class on how to make mosaic shapes hundreds of times now. I will be happy to see it on the wall.

Whirligig: You plan to install next week. . .

Elizabeth: We have two walls and a tunnel. We are hiring professional tile installers because it is so big and heavy. I will be there as support. I don’t know what problems we will encounter, but we will have problems. We already fixed a few things–the walls were uneven and there was an anti-grafitti sealant on one wall that would not allow the tiles to adhere, so we had to remove that.

Whirligig: Tell me about your painting work.

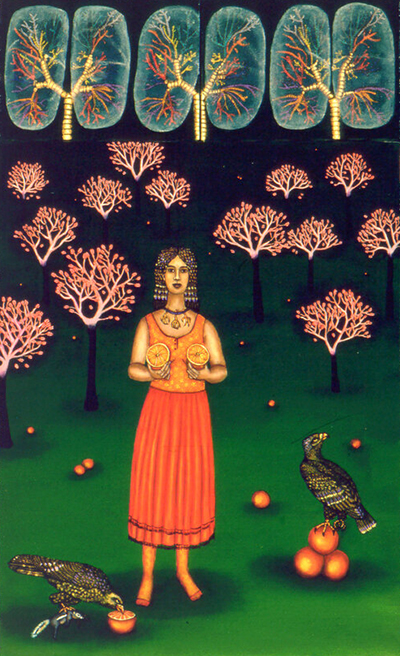

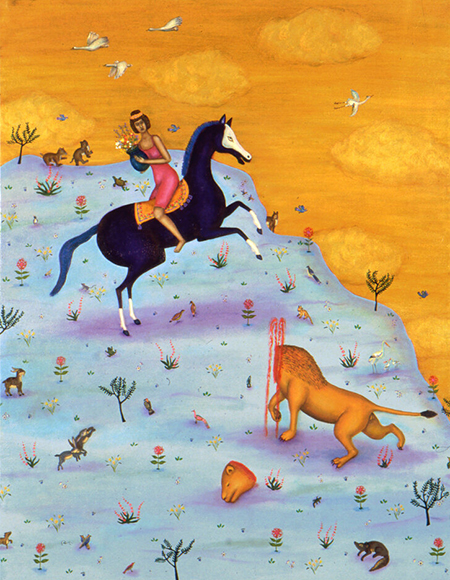

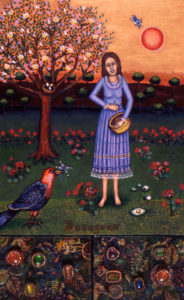

Elizabeth: My work belongs to the Mexican tradition. I like surrealism. I like animals and nature. I like a lot of handmade patterns and decoration. I have been working on a collection called Madre Tierra (Mother Earth). They are women with the face of an animal. Very surreal. They represent the need to care for the environment. The most recent is Mother Earth Crow. She is signaling with her wings the end of the wilderness, saying “From here to here is wilderness, so you don’t build. And from here to here is for humans, so stay on the human side.” They almost look religious. They are big animals with dresses, in nature. One is Vindictive Mother Earth. She has humans in a cage. Bird Mother Earth is teaching little birds how to protect themselves against us. But all very beautiful and colorful, filled with flowers. Mother Earth Wolf is planting flowers on the pavement in Mexico City. She is taking care of them with a watering can, a nurturing Mother Earth.

Whirligig: Those are in acrylic, oil?

Elizabeth: I love to paint old style, oil on wood, because with painting in glazes it becomes very jewel like and medieval. You can touch the colors.

I’ve also illustrated many children’s books. I just finished a book on El Salvador, ABC El Salvador.

Whirligig: Are there specific artists you are inspired by or look too?

Elizabeth: Sometimes I am a bit sad that the person most known here is Frida Kahlo. When you see Frida’s work it’s not only Frida’s style, but it is Frida’s style on top of the Mexican tradition. Her work makes a lot of sense within Mexican art. When she was painting there were a lot of women painting. For example Leonora Carrington and Remedios Varo. There was a magical group of women painters that had this surreal, folksy, decorated, colorful work. I really like their work. Because I grew up in Mexico City it was normal for me to visit Frida’s house or see a show of Remedios Varo and other artists from that time. I don’t try to do what they do, but I like the visual language they were using. My own work is always about nature and the environment.

Whirligig: Would you say that you are mostly inspired by female artists?

Elizabeth: I would say that I really like their quality. I don’t want to generalize, but with Mexican women artists there is something that is, to use a trite word, feminine–care taking, nurturing and smaller–that I like. The famous male Mexican artists are very grandiose, “Industrialism came to save us! The workers will save us!” Full of big ideas, but with little heart. I like works with more heart. I am not saying that men cannot do this, just historically in Mexico it has been the case that women pay attention to heart.

Whirligig: You exhibited sculpture in your Art Kiosk show.

Elizabeth: I do a little bit of everything. I have created three installations with ideas of nature and animals. At the Oakland museum for the Day of the Dead I showed dead animals. I made a coal circle . . . where it is clean the animals are alive and flying. Where it is dirty the animals are dead.Â

Whirligig: What is it about working with animal symbolism that you hope to communicate?

Elizabeth: I sometimes feel that we humans do not believe that animals have the same right as us to be here. That we are more than they are. That we own this place. After all of the facts telling us this is not the case, global warming. . . I want to be a voice for animals, even if it is a small one, saying “We are here. We belong. This is also our earth.”

Whirligig: So you grew up in Mexico City . . .

Elizabeth: Yes. I did most of my formative years in Mexico. I came here after I got married. I have been many years now here in California.

Whirligig: How is it to be an immigrant here in California?

Elizabeth: Sometimes it’s good, sometimes not so much. Especially if you are from Mexico. My husband is from Argentina and he does not cross too many people with stereotypes about what an Argentinian is. Maybe they know about the tango. . . But if you are from Mexico the stereotypes are very, very, very strong. Sometimes when I encounter someone who knows only that I am from Mexico and nothing else about me, I feel discriminated against. For example, people who don’t know me immediately assume that I am not educated. They talk to me as if I didn’t know things. This actually happens a lot. I am not saying that everybody needs to be educated, but oh my gosh, they speak to me in such a way that I want to say, You know I have a graduate degree you don’t have to talk to me as if I don’t understand things.

Whirligig: Because of your accent?

Elizabeth: My accent for sure, and then they ask me, Where are you from? And I say, Mexico. In my life in California I have been hired at least three times as a babysitter. I would be with my children and they [some stranger in public] would assume I was a nanny. It was hard for me to convince these moms that I was also a mom and not the nanny. They would ask questions like, “The children speak Spanish to you?” And I would say, Yes. Then they would say, “That’s wonderful. Other nannies I know speak Spanish to the children but the children do not speak Spanish back. Do you have a driver’s license? How much do you charge?” They would be so surprised to find out I was the mother and not the nanny. Some assumptions are stronger than you think. In daily life doors can close easily because people have very strong stereotypes about what a Mexican is. I moved to a new neighborhood and the next door neighbor told me, “I don’t want to be discouraging but Mexicans are moving here. . .” Things like that happen here and there and everywhere. It always surprises me because most people are nice and good. But those who are rude and not nice. . . they don’t know me, I don’t know them. . .

Whirligig: Part of it is being a woman. . .

Elizabeth: Yes. But why don’t they just ask me what I think rather than thinking I don’t know anything? Sometimes people start sentences like, “Here in California, we. . . ” immediately making me the other. I’ve been here 30 years. I can say, We in California. . .

I like so many things about Northern California, but when I face those discriminating people I don’t like it.

Whirligig: I’m sorry that is here.

Elizabeth: People don’t know that if you have an accent you are asked a lot, Where are you from? How long are you staying? If it were a neutral question . . . but when you are asked that on a weekly basis it makes you feel as if you don’t belong, you don’t belong, you don’t belong. It makes you feel there is a wall around you everywhere you go. Now when they ask me, I ask them, And where are you from? Tell me about. . . We all are from somewhere, even if we didn’t cross a border. I try to be light about it but I wish it wasn’t the case.

Whirligig: You’ve been working on a two plus year project. What will you do after?

Elizabeth: The park has asked me to make some individual animals. It will be only me in my studio. I will have control of everything. I am looking forward to that. Then I will paint. I have loved doing this, but it was a lot of heavy lifting.

Whirligig: It’s an important project.

Elizabeth: I love that we have so many community members taking part, and also, if someone came to a workshop and made a piece of the mural, it is included. I didn’t get rid of anything the volunteers created. I kept my promise, that “if you learn to do it, you are a part of the mural.”

Whirligig: Do you think there was anything in your upbringing that made you particularly tune into non-human animals?

Elizabeth: My grandfather was a farmer. He could barely sell his cows because he loved them. He named them and the chickens and the pigs. When buyers came to take them, he had so much trouble. They followed him like dogs. He was a bad farmer in that sense. I think growing up with him I fell in love with the animals just like he did. Growing up in Mexico City, nature was so devastated by pollution, 20 million people in one city.

One day, everywhere I went, there were dead birds. Something was happening in the air or poison. Walking to school that day was one of the most important days of my life. I realized it was not a normal day. This was human induced. I think I became an environmentalist that day. Later we heard it was a paper factory that did not have proper air filters. They polluted the air. The birds died. . . It really welded a before and after for me.

Whirligig: Do you have a spirit animal? Is there a particular animal you are closest to?

Elizabeth: Not really. I strongly believe the earth would be better off without us. We are the extra animal.

Whirligig: Agreed.

Elizabeth: Even sharks and insects have a right to be here. I’m a little bit of Buddhist in that sense. Everything that is living has a right to be here.

What makes me really happy is that I have found many paths to follow and they have taken me to incredible places that I never thought I could go or do. My parents were very sad when I told them I wanted to be an artist. But I am so happy that I am. A perfect day for me has art and nature. I have lived my life like that. And Northern California is a beautiful place and people respect nature here. People are also more open. I know that the Bay Area is the right place for me. Here I can blend in. California has a very nice collection of Asian art and Latino art and Californian art and good food.

Whirligig: How are you feeling now that the mural is up and complete?

Elizabeth: It was a tremendous amount of work. I am exhausted. I am happy.

Whirligig Interview by Nanette Wylde.

All images copyright and courtesy of Elizabeth Gómez.

Elizabeth Gómez’s website.