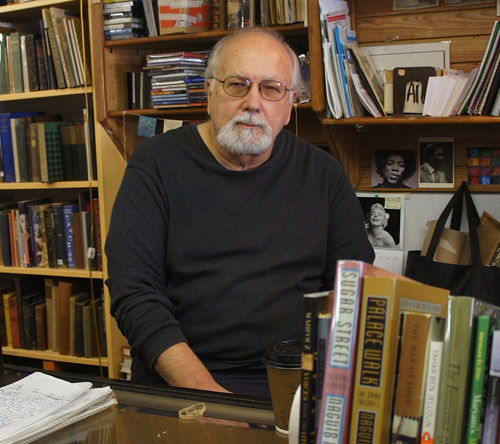

Sinjin Jones is a transmedia artist, storyteller, and poet interested in the connections between diverse media forms which allow him to combine these in interesting ways. In 2019, shortly before the reality of a global pandemic, Jones became the Executive Artistic Director of The Pear Theatre in Mountain View, California.

Jones has a long history of engaging in live performance. From his student days until he moved to the Bay Area, Jones spent his summers working for A Theatre Group in Silverton, Colorado where he wrote, directed, and eventually became their Artistic Director and Vice President of their Board of Directors. He has founded a non-profit, multimedia artists’ collective called Otherworld Collective; and co-founded Perplexity Pictures, a film production company. He has a background in teaching performance arts at all levels, and is currently teaching for The Pear’s outreach programs. Jones has a Bachelor of Arts in Theatre, Film, and Video Production from the University of Colorado, Denver; and an MFA in Creative Writing from Regis University.

At The Pear, Jones is developing dynamic, engaging, and fresh programming that both surprises and challenges.

His leadership consistently demonstrates his rich intellect and deep investment in local communities. We spoke over tea at an outdoor cafe on a lovely spring afternoon.

Nanette: How did you come to theatre?

Sinjin: When I was a kid I would tell stories to myself. We were very poor and didn’t have access to theatre. We would go to the dollar store and I would get to pick out one thing. I would pick out a [cassette] tape because my mom had a radio that also had a tape recorder. I would go into my room at night and tell stories to myself, improvised stories. That turned into getting together with the neighbor kids to tell stories. I would write stories and we would perform them. This was second and third grade, and I didn’t really know what theatre was, only to some small extent. Then my elementary school turned into a school of the arts and I got to take some theatre classes. I think that’s the beginning. I consider myself to be a storytelling artist, but that live act of performing in front of people or seeing story come to life in person has always interested me. That’s really the start of it all.

More formally, I did theatre in high school. I was deciding between archaeology and theatre/film for college. The University of Denver had a program where you could do theatre and film at the same time, so I was sold. The idea of storytelling is really beautiful to me. I’ve practiced a lot of different forms of art, many are less collaborative than theatre is. I like the coalescence of different artists from different backgrounds and different skill sets coming together to create one unified portrait of something.

Nanette: Did you grow up in Colorado?

Sinjin: I did.

Nanette: Denver has a really good art scene.

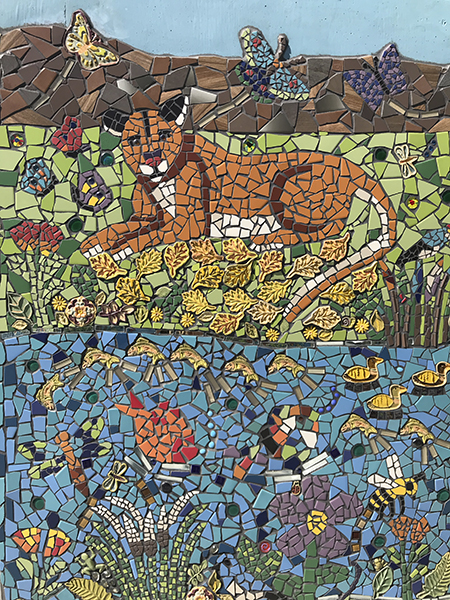

Sinjin: They do. I am very lucky. Downtown Denver has a ton of public art. In college, one of the assignments for one of my theatre classes was, “Here’s a map of downtown Denver. Go see as many of the public art pieces as you possibly can.” That is very lucky. It’s nice to have a lot of public art to experience and just be around.

Nanette: You demonstrate an immense amount of theatrical knowledge, and it is apparent by your presentations that developing a contemporary and engaging season requires broad and deep research. What is your process from seed to completed season?

Sinjin: It’s long is what it is. Let’s take this season as an example. I started having conversations in July of last year; before we had started the current season. The start of it is asking what interesting things are happening in the world of theatre, around here, around the country, around the world. . . and just staying with a weathered eye on cool people doing cool things in my network. Some of those are people I have worked with, some are artists in theatres that I find to be aspirational for The Pear or for myself as an artist. Some of them are a variety of artists I would like to work with someday. Part of it is: what are these artists doing, what is Broadway doing, what are the fringe festivals doing, what are off Broadway theatres doing.

I haven’t been in the Bay Area very long compared to most of the artists I’m working with, but there are a group of artists who will share with me interesting things they see or hear if they have a chance to go to New York. Some of them are like, “If there is something you want to know about, tell me before I go and I will see that show.” Because I don’t get to go to New York as often as I would like. If The Pear were a bigger theatre it would be different. Also, in pop culture, what is the trend in performance art, time-based art, media formats that are single person-based but more crowd facing—what are people doing there. That’s how it starts. Then reading the current seasons of many other theatres around that I look up to like Aurora Theatre or Berkeley Rep or Shotgun—theatres that I respect that have a different perspective on things. Denver Center is one of those. Each year I see their whole season and I read all of those plays.

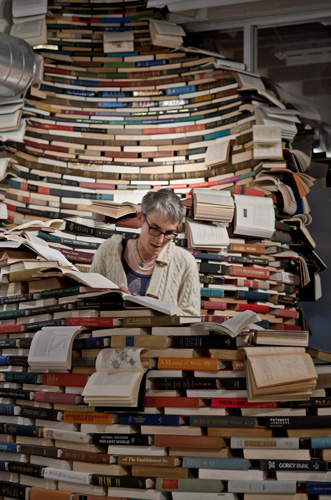

The fall is just reading as many plays as is humanly possible. Every year I read at least 50, maybe closer to 100 new plays. That’s not fully reading. If I read a page and it’s not. . . I won’t force myself to read it unless it’s a recommendation from someone who is saying, “I really want you to read this.” Then I will read more even if my vibe isn’t with it. Full plays, at least 50 every single year. It’s about seeing what strikes and feeling out what is inspirational.

We are coming off of a season that is highly theatrical—plays that are exploring theatricality in a different way. We’ve learned that what is most successful for us is when the audience has a sense of awe coming into the theatre. At The Pear, you never know what the arrangement is going to be. Hopefully, people are starting to have trust in the work that we do. I wanted to lean heavily into that with this upcoming season. We have a lot of plays that are historical in nature. They take stories from the past and connect us with that history by taking those stories and exploring them in an interesting way. That is what grounded this upcoming season.

Last season we took the idea of driven characters and the concept of theatrical experiences. We chose a bunch of finalist plays. I whittle down all the plays [I read] to a group of about 15. Then I get a bunch of community members together with the whole Pear staff and the Board Members. They all have to agree to read at least half of the plays and write a little blurb about each. This year was our largest group, 16 members. Then we have a meeting.

I believe in healthy conflict. People are arguing which play is the best. My job, in that context, is listening because at the end of the day we are a community-based theatre. I want to make sure that several of the stakeholders in our community are really excited about the choices. Then it’s logistics—can we get the rights, how expensive is it to produce this show, how does it fit in the larger scheme of things. This is the less artistic and more practical side of things where we start to move things together and collapse things that work and things that don’t work.

We are lucky we don’t do a ton of plays that other theatres are thinking about before us, so we don’t have competition all of the time. But you never know. We applied to do The Agitators two seasons ago and didn’t get the rights. I think because there was a West Coast Premiere in the Central Valley. That sort of thing will dissuade us from doing a play.

Nanette: You have to apply to do a play?

Sinjin: Yes. There are three big licensing companies. Some you just pay and you get the rights. There are plays that are newer or have a hold on them for some reason. For example, we applied for a play called Passover. It has two black men in the ghetto sitting on a street corner waiting for someone to come. It takes that Waiting for Godot vibe, but puts it firmly in a Black perspective and what it means to live a hard life in the projects. We applied for those rights and then it was announced it was going to Broadway. In that situation it can’t go anywhere else in the country because Broadway gets exclusive rights.

It’s not guaranteed and we do pay a lot of money for rights. Musicals being the most expensive with fees for the music, books and other stuff that is licenced. Love Letters (in the current season) is one of the most expensive shows we’ve had. I don’t know why, it just is. It can range from $100 to $250 per performance. A mainstage play might be two to three thousand, a musical might be six to seven thousand to produce.

Nanette: When you say driven, do you mean character driven v plot driven?

Sinjin: Yes. This season we had a mix of character driven and plot driven shows. Noises Off is a show where the characters are interesting, but things are happening. I would argue you’re equally interested in the plot of the show as you are in what the characters are doing. For Peter Pan on Her 70th Birthday it is the characters driving the story and there is not a ton of plot.

I’ve been looking at very powerful characters who have control of their own destiny, whether as heroes or as villains. Folks who are pushing hard to make a change—to change their world or the world at large, to fix something. Then to take stories focused on what choices the characters are making in the world and not on what things the world is doing to the characters. That sort of structure is not about spectacle, it’s about the struggles that exist in everyday life, whether it’s on a big scale or small scale.

Nanette: Is the casting more of a challenge in a character driven play?

Sinjin: I think so. I would argue, and there are people who will disagree with me on this, that character driven plays have fewer big elements to distract you from the things the characters are saying. They tend to be very language heavy. If an actor is not embodying the character in a way that is believable and exciting, you are going to notice it a lot more.

One of the goals for this coming season is to lean hard into the incredible South Bay talent that we have, in terms of casting, and to put the actors at the forefront, as opposed to covering things with spectacle and pushing through with big, larger than life things. . . focusing on that personal journey. For sure it will make casting harder. We have our first open call for auditions this coming weekend. We are very happy and honored that we are full for in person auditions. We are expecting another 60 folks to submit online. We tried to promote “first” auditions early and eagerly. We are very lucky that people are showing up. I am a very “actor first” director. I am very excited about this but it will be a big challenge for us considering the scope of where Bay Area theatre is right now.

Nanette: Your role as Executive Artistic Director at The Pear is extremely complex, much more than selecting each season’s line up. What are the joys and challenges of this job?

Sinjin: I am happiest in moments when I come into rehearsal for a show that I am not directing and I feel enraptured by theatre. It’s why I do this. It’s being connected to something larger than yourself. That’s why I am in the arts and why I love theatre.

In the midst of all the logistics for my job to function and for the theatre to function, it is those moments that make me feel so lucky that I get to do this everyday. Especially in the Bay Area where many people do their jobs as part of three other jobs they have to do to make ends meet. I am very very lucky.

Those moments when I come into a design rehearsal or a director rehearsal—I’ll be doing three things at once, taking notes, and I’ll look up and Wow. Something happens on stage that I am not expecting and I get to see it. That is a beautiful moment. I get to experience that more often than most people. I get to flex my artistic muscles in many different ways. That is a very rare privilege. If I want to act, I can act. If I want to direct, I can direct. If I want to design, I can design. I get to create professorial conceits for a production. I get to see that play out.

The hard things. . . with non-profit theatre in general and certainly right now, there is a looming sense that maybe not around that corner, but around the corner around that, there is just utter destruction. There is stress and anxiety. There is, we’re okay now, but there is no guarantee. There is the artistic director job which is creative and production based, and there is the executive director job which is we need to find money to fund all of these things. The granting landscape, which isn’t all that reliable here in the South Bay, makes us reliant on fundraising, and hoping that the work that we are doing is appealing to our donors. So far we are honored that we are continuing to meet our fundraising goals collectively.

It’s doing interesting and artistically challenging work while trying to make sure that people are excited to come see it. To take artistic risks in a climate where a lot of audience members are taking less risks now than they were before the pandemic. It is a very risk aversive environment for a lot of theatre patrons.

The people who are coming to see shows at The Pear, in my qualitative and quantitative experience, are enjoying the shows. The number of people taking the risk and coming to see shows is lower than we would like it to be. In the meantime we have the grant landscape and the donor landscape and the patron landscape, a sort of tripod to keep us from falling over. That’s a precarious balance. It’s the balance of every non-profit. . . There are some anxiety ridden days. That’s the most challenging, the general non-profit vibe.

Nanette: Theatre is highly collaborative. What makes it work and what hinders a successful production?

Sinjin: At The Pear, by necessity we are All hands on deck. We don’t have a luxury of staff that can work in a single domain. Everyone is on board for everything. For theatre to work successfully it has to be a spirit of collaboration.

My ideal version of theatre is when a director has a strong collaborative vision and an understanding of how to execute that vision. Which is to say the director is the conductor on this train. We need to know where the tracks lead, but every artist on that team has something very interesting to add in the direction that we are going. The most effective way to go about those things is when the director says “I have this really exciting idea. I want to share it with you. What are the ideas that you have based on this idea?”

We try really hard to set up a situation, the guide rails, so that directors feel empowered to create that strong vision and feel excited about collaborating on what direction that vision might take. We are in a place in theatre where the idea of top down leadership is just not a thing. Or if it is a thing, it’s very much not in the mainstream consciousness as it may have been in the 90s and 2000s. I think that leading from behind or leading from within is a far more effective structure. That’s what pushes the elements of theatre forward. That’s what pushes productions from being good to being great. Or from being great to being awe-inspiring. That’s my goal in theatre. It’s to feel that I’m connected with something larger than myself as often as possible. If everyone is committed to that goal, and everyone feels they have a voice towards that goal, that is perfection.

The most successful productions we’ve had are when the team members are saying ooh what about this. . . In full disclosure I’d like The Pear to teeter on the precarious precipice of “can we do this or can we not do this?” For a group of artists to ask the question “What if?” and for us to set up a situation where the artists want to ask the question “What if?” is a beautiful thing. Everyone is on the edge. Can we do this?

Sometimes the answer is no at first and yes later. Sometimes the answer is I don’t know but let’s try. If everyone on the team is firing on those cylinders—that is the best example of what makes powerful theatre—it means that everyone is artistically engaged. It’s not just people coming in to execute a job. It’s people coming in to do something they are passionate about. To me, that’s what defines the arts in general, and certainly theatre.

Nanette: This is a quote from your CV:

“In those brief moments where one encounters a piece of art, whether it be as simple as a single note or as complex as a symphony, and is caught up entirely in a subtly profound sense of awe, it is then that we are closest to the original intention of storytelling.”

I totally agree. How are you able to bring that type of magic into live theatre?

Sinjin: That’s hard. My original and most interested form of study is in this concept of the sublime. This concept of connecting to something larger than oneself. There are traditions of theatre that are about this idea, about the ritual of theatre. In that there is some magic.

The times that I feel that theatre is actively achieving this is when you have a story that is both accessible and challenging, written by a playwright who had personal connection to the story they are telling. You have a cast that has a personal connection to the work they are doing whether that is subject matter based or process based. You have a process and consequently a director who has that same intimate connection to the work, but also has brought something of themselves and laid that bare as part of the work. You have designers that have brought a unique and fascinating angle to the perspective as well, but it is more often not noticed, it is subtle and there. All of that is half.

The other half is an audience, it could be one person, that is for whatever reason, a little bit more open. An audience that is able to take a deep breath at the beginning, and then exhale to be connected with every other person around them. With that sort of perfect chaotic and symbiotic situation, that occurs in that unpredictable way, that’s what makes theatre the perfect expression of the sublime in that singular moment. I think this happens to people when they are experiencing art one-on-one and they feel enraptured, or when listening to poetry. It happens in film a lot because film is a fully sensory form. The unique thing about theatre is that you are not alone. It is not a singular experience.

I’ve been in such magical situations when I am sitting there and there is an acknowledgement across the whole space that magic has happened and you have been transported to a place—emotionally, intellectually, spiritually—that you were not expecting to go even if you were open to it. That to me is the perfection of theatre. When theatre is performing at it’s peak, it is maybe the one place that is designed for that collective experience. It comes from an oral tradition, right? and it ignites that ancient, primal experience that we have when we connect with something older. But then it can connect with something new, the frontal lobe brain intellectual concept. I would like to do a PhD on the sublime.

Nanette: Is there one favorite role/play/performance that continues to resonate with you?

Sinjin: When I was in my senior year of undergrad I was working with Laura Cuetara, one of my two incredible directing mentors. She is a wild human being and directs in a very organic style. We got the rights to do the first authorized adaptation of The Handmaid’s Tale. This was an insane production. There were about 35 people involved. We had a German style opera house theater at the University of Denver. We took out the floor and built staircases so that it was in the round. There were things happening in the rafters, bodies hanging. I remember being in the booth calling the show. I was watching the armed soldiers in the opera house, Ofred escaping the chaos of this immersive situation. My job was to keep this production together and to provide a sense of stability with this complex, 50 plus person crew and cast. I remember feeling . . . I still get goosebumps remembering that production, how impactful it was on my aesthetic and my interests in the artform in general.

At The Pear it was much smaller. It was back in January 2022. We were doing Mountain Top and Sunset Baby in repertory. We were live for a while. I was with three wonderful actors. It was so small and so intimate. We were working on these two very difficult but very impactful plays. It was in this realm of ritual. I’m a big fan of ritual based practices theatrically. We did some hard work that was incredibly emotional and so challenging. I was working with actors to push them very hard, but in a safe and contained way. It’s that hard work you have to do with a play like Sunset Baby where the lead character, Lena, has lived through so much trauma. We need to lay that bare on stage and see her come across as a powerful woman. To work with incredible actors in that space; those moments sit with me. Mountain Top is such an important play about the real Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and not the image of that person. Those moments in those rehearsals where I felt surprised and shocked by what actors were able to conjure up from inside of themselves is just remarkable. Those are two that I would name for sure, but there are a lot.

Nanette: This concept of repertory where you work two plays together. Where does that come from?

Sinjin: What I know is that it is a pretty common thing in Shakespeare companies. If you have a summer stock experience or you have a group of people working just for the summer, oftentimes you are paying them for their time so you want to be doing full time work, so they would do Shakespeare plays in repertory. You have the same ensemble doing two, three, four plays in rep to attract different audiences, but also to keep them busy. It is less common for non-Shakespeare theatres to do repertory shows with the same acting ensemble.

We did it for our 20th anniversary season in 2021. It was about talking to our more traditional Pear audience, saying these are the plays we’ve done in the past. Let’s put them in context with the direction we might be heading. We chose plays that The Pear had done before with plays that The Pear had never done before. We found that the actors and the directors and the crew find this to be a unique type of experience where you are contextualizing each within each other. The shows are giving perspective to one another in ways you don’t often get. It allows for the opportunity to explore two or three really different roles as a performer that you wouldn’t get to explore in context of one another. When done well, it is both a logistical nightmare, and an enriching experience for the audience and the crews involved, as the shows provide influence to each other. You might get sucked into one play or the other, but once you’ve seen one you want to see the other. It might be that you want to see an actor do a different role.

It’s a long tradition, repertory. It provides some logistic ability for our theatre to do more shows while giving our staff a little bit more space.

Nanette: I’ve noticed that The Pear does Shakespeare regularly.

Sinjin: Here’s what I believe about Shakespeare. I am a fan of Shakespeare. I do not believe that The Pear is a Shakespeare company. There are many wonderful Shakespeare companies in the South Bay. While I am leading The Pear, I am of the belief that we should only do Shakespeare for the purpose of contextualizing it in an interesting way. That doesn’t mean we can’t do traditional Shakespeare done traditionally. It means that its important to me to have something to say about it and that means contextualizing it and creating something that feels like it can make Shakespeare accessible for a non Shakespeare audience. Because I don’t think Shakespeare is for everyone. When we do Shakespeare I want people to leave the theatre finding it unique enough, transforming enough, that they found it interesting.

Nanette: Do the arts have/carry responsibility to encourage or further cultural dialogue?

Sinjin: My basic answer is, Of course they do. I certainly think it is my responsibility and The Pear’s responsibility to facilitate the conversation towards moving our community forward in the ways we talk about certain things. We try to be a culturally responsive organization in both the shows we produce and how we produce them. If we are going to do plays by dead white guys we want to put them into context in a larger perspective in a way that enriches our community. That also means that we are generally going to choose plays and perspectives that are traditionally excluded from the conversation. It also means that I am super interested in stories that are going to challenge our audiences in ways they maybe didn’t even know they needed to be challenged.

I’ll give an example. We did Mountain Top and Sunset Baby. Those are really heavy in the Black drama sphere. Those are hard plays about hard things that happen to Black people. I am a Black man. After doing those shows I was a little bit exhausted. There are so many plays about trauma from the communities of color, from queer communities. I was really exhausted and I didn’t want to see it in the next shows that we did. So we did Dontrell Kissed by the Sea which had Black people but it was about centering the joy rather than centering how hard life can be. That’s some of the reasons for the shows we are choosing. Yes. The trauma exists but how do we also feature actors in different stories and explore all the nuances that exist in different cultures.

I think it is my responsibility to look at the whole swath of our community and how they can be represented, and also to tell engaging stories so that other people can understand what it is that different communities are going through in equal measure with what those communities have to offer if you haven’t experienced them. That includes a lot of learning. For me it is our duty and responsibility to help our community progress and process. There is a reason why we are doing The Agitators after the election.

I think it can be helpful for us to be reminded of where we came from in order to help us contextualize where we must go. Who knows if we will have any answers. Posing the questions is an important aspect of the work that we do.

We shy away, perhaps to our bank account’s detriment, from doing crowd pleaser plays for the sake of crowd pleaser plays. We ask, how can we do interesting plays with interesting perspectives. We also want to play with the way we cast those plays so that people can feel enriched just by the type of people they are seeing on stage, in addition to the style we are producing it in.

Nanette: You have an MFA in creative writing and a long history as a poet. Are you still writing poetry?

Sinjin: I am. A lot of the work that I do tends to be transmedia at this point. I have a sort of entity called The Foundry of the Ether. I wrote a poetry album and then recorded that poetry album. I then sent that poetry album separately to musicians and filmmakers, and had them separately create visual components and auditory components. Then collaborated with an artist friend to put those components together to create a visual poetry album.

I am working on my first poetry book right now. Well, I guess I wrote one for my MFA, but I’m not sure that counts. I’m writing a poetry album that is more spatial. It’s set in a room and laid out as a room. It is weird. I’ve been working on this for a while. One of my major goals in life is to find a better balance between theatre and my more personal projects.

So, yes, I do work on poetry actively as well as film making. I made a short film in 2021 and in 2022, as well. There is a symbiotic series that I have going on that’s about symbols.

It’s important for me to keep active in these other formats because I think it keeps my theatrical life alive. Hopefully what my directing craft holds is a variety of context that is attributed to the other artforms I create with.

Nanette: What is the future of live theatre?

Sinjin: No one has ever called me an optimist. I am not a pessimist. I think I am realistic. I think I am pretty honest. Theatre has a vibe which has been happening for thousands of years. There is no reason to believe that theatre as an art form is going to die. I think that it is imperitve that theatre as an industry changes dramatically in the next 10 to 20 years in order to greet a lot of the technology that exists in our world now and the next five years. As an industry theatre has never been that great at treating artists well or respecting people’s time. Part of that is very American based, because we don’t fund the arts that well here. In many, if not most, European countries there are artists’ funds and a lot of ways to do theatre work in its more traditional forms that is funded by the government. That just doesn’t exist as much here, or if it does exist there are many more difficult hurdles to jump through to get that funding. The pandemic, especially in the South Bay, has opened people’s eyes to the unsustainability of what the theatre art form does. That’s really challenging. It’s challenging the status quo in a way that I think is really important. How we pivot the “model” of theatre in order to greet that is really important. Artists should be getting paid more for what they do. That has always been the case. How do we get from where we are to where we need to be is the million dollar question. Literally. There has already been a dramatic shift in the way artists are treated and that is imperative and the most valuable thing we can continue.

How do we greet the fact that AI is a big thing. Technology provides a type of immersion that for people in my generation, as a millennial, is much more accessible—I’ll tell you definitively as a theatre person, it is an easier sell for me to spend $100 to go to a unique immersive experience that feels one-of-a-kind, than it is for me to spend the same amount of money to go see a show that I’ve seen before. And I’m a theatre person. Theatre is my job and I love theatre. So, if I’m not a theatre person, that cost benefit analysis is so hard. Perhaps that will change.

Historically theatre audiences have always been older. Perhaps as millennials get older they will have more interest. My generation is the first generation that grew up with computers, right. So I don’t know if that is going to get better. The industry has some really important questions to answer about what role we want to play in the artistic sphere. How we make it accessible for artists to survive, and also how we engage a generation of new theatre goers with new tools that we haven’t used in previous generations. I think it can be done.

The reason all theatres are in this really hard financial place right now is because they are not set up for our current environment. What that future will hold, I don’t know, but I think it will take some re-invention. Theatre has reinvented itself many many times, so there is nothing that says it can’t be done, but I do believe that it will take some concerted effort.

Whirligig Interview by Nanette Wylde.