Judith Selby Lang’s website states that she “is an artist committed to the creation of positive symbols and life-affirming images to help energize the conversation about social, political and environmental issues.” This is a perfect description of the uplifting and transformative nature of her multi-dimensional art practice as well as a reflection of her demeanor and personality—creative, positive, life-affirming, energetic, and openly communicative about critical concerns that affect us all.

Lang’s work includes artist’s books, mixed media objects, and a wide range of projects using plastic debris collected from 1000 yards of one beach on the Northern California coast. Lang has an extensive exhibition history. She currently has a large scale beach plastic installation in The Secret Life of Earth: Alive! Awake! (And possibly really Angry!) at the American Visionary Art Museum in Baltimore, Maryland; and will be showing in The Great Wave: Contemporary Art about the Ocean at the Bedford Gallery in Walnut Creek, California in early 2020. Her current project is creating a wedding dress made from recovered plastic bags for exhibition in Castaways: Art from the Material World at The Bateman Foundation in Victoria, British Columbia, which opens in Spring of 2020.

Lang has a BA from Pitzer College and an MA in Interdisciplinary Studies in Creative Arts from San Francisco State University. She spent many years teaching art in a variety of North Bay (California) venues before turning her focus to the studio full time. With a barn full of beach plastic—washed, sorted and boxed—collected over the years, Lang has an immense body of work, both independent and collaborative, which reflects our times while engaging viewers from all walks of life in conversations regarding possibilities for improving our environment.

We visited on a bright fall afternoon in her rural Forest Knolls studio, just a short drive to Kehoe Beach.

Nanette: How did you come to art?

Judith: Defining myself as an artist was a long time in coming. I thought I would never have the patience to be an artist. People have this preconception that art is a wild and spontaneous activity but don’t know that after the flash of inspiration sometimes a long and tedious effort is required to realize the vision.

I grew up in a family that was art friendly. My dad and mom both painted. We went regularly to the art museum. In 1962 my parents took me to the Dallas Museum of Art where I saw Andrew Wyeth’s painting That Gentleman.

The painting drew many to the museum—there were long lines with stanchions and velvet ropes to control the crowds. Was it because curious onlookers wanted a glimpse of a painting of a black man? Mind you it was a simple scene of a black man seated, in dusky light, in a moment of repose. It’s of Wyeth’s neighbor Tom Clark. To me it seemed a radical move for the museum to exhibit a painting of a black man especially at a time when segregation still existed in the South. I remember water fountains with signs for whites only, for blacks only. This was 1962, years before the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the Civil Rights Act of 1968. Perhaps it was the shock to the public that the museum had purchased the painting or maybe, it was, as I would like to think, that there was tremendous interest in seeing a masterwork by a great American artist. Either way there were people, lots of people waiting for their turn to view the painting.

The line moved slowly in a kind of reverential prayer and when it was my turn I stepped up in front of the painting to gaze with wonder not only at the power of the image but also the incredible finesse of the brush work. Something in my young heart was deeply moved. At that moment I made a commitment to art. I made my pledge to become an artist. That an image could have such an incredible impact on me and the people who had come to the museum was something that I too wanted to accomplish. On that day, at age twelve, I knew that I wanted to do something that would make a difference—to make art that would shine a light on injustice in the world.

Nanette: That’s a beautiful story Judith.

Judith: I visited That Gentleman in the 80’s and again in 2012. Each time as I have stood before it, with welling tears, I have reaffirmed my commitment. Museum staff reports That Gentleman is one of the most beloved works in the collection.

In 2012, my husband Richard Lang and I were invited to give a lecture about our beach plastic project at the Dallas Museum of Art. To present our work just steps away from That Gentleman was a giant step towards realizing the commitment I had made that day in 1962. I never could have imagined that 50 years later, picking up trash from our little stretch of Kehoe Beach would shine a light on a devastating global environmental problem and would take me back to Texas.

Nanette: How long did it take you to realize you were an artist and to start making art?

Judith: For undergrad I studied at Pitzer College in the Claremont Colleges and spent my junior year at CalArts. So I was well on my way in my training to become an artist. But, when introducing myself, it took me a long while to actually call myself an “artist.”hat came much later. I was shy to take on that mantle.

Since it was a time when everything was free-spirited and experimental in school I didn’t learn the basic skills of drawing and composition. Fortunately, I found Joseph Query, a private teacher in the Napa Valley, who I spent eight years with, learning traditional skills of drawing, clay sculpting and plaster and bronze casting.

When I graduated from college, I did not envision working with the elderly, nor could I ever imagine that it would become my life work. But real academic art teaching jobs were scarce, so when a Napa Valley College position teaching “art” at Napa State Hospital was offered, I jumped at the opportunity. I had no teaching experience. I was not trained in art therapy. As you might imagine there were not a lot of folks clamoring for tough jobs like working in a mental institution. We were given some on-the-job teacher training, but mostly we were on our own to develop lesson plans and art projects. My first students were severely disabled so my teaching was even more basic than basic, like teaching someone how to pick up a pencil or how to make a mark on the page. It was rough going, but I cared about my students and learned from them. I learned patience, the necessity of patience, when working with people with mental and physical challenges. When the population at NSH changed, I began working in convalescent hospitals, senior centers, assisted living facilities with students with Alzheimer’s, cancer, stroke, hearing impairment, dementia, Parkinson’s and on and on.

I taught for 35 years in a variety of situations, mostly in adult programs through Napa Valley College, College of Marin and Santa Rosa Junior College. The pay was adequate and met my financial needs. It gave me economic stability and allowed me to do my own artwork without commercial consideration. Plus, it gave me an opportunity to share my enthusiasm for the creative life. I like to say that I was the midwife to my students creative process. Most of my students had raised families, had jobs and other responsibilities. They may have wanted to paint but it was not until their Golden Years that they finally had the chance. My approach was not in teaching art with a big “A.” I’d say, “Let’s just try putting the paint on the paper in a beautiful way.”

Art for me has been a saving grace. I have been able to find meaning through personal expression, and, I hope that I have been able to help others find their meaning through art.

Nanette: How did you come to the beach plastic work?

Judith: In 1996 I was teaching for the College of Marin in a convalescent care facility in Tiburon. Every Monday, for lunch I would go to Blackie’s Pasture where I would sit on a park bench and gaze across Richardson Bay enjoying the view of the dramatic skyline of San Francisco.

Tangled in the strands of seaweed I was surprised to see pieces of plastic. The shapes and colors were intriguing so I started collecting them and making little Surrealist-inspired sculptures.

As a book maker/designer I was working collaboratively with painter, Jackie Kirk, and poet, Barbara Swift Brauer. Extensive research about which printing press in the Bay Area could best accomplish one of our projects, pointed to Trillium Press in Brisbane as the premier producers and publishers of limited edition fine art prints.

After numerous phone calls and scheduling with David Salgado, finally a date was set. I brought our mock up ready to get an estimate on papers, printing, typography and binding costs so that we could prepare a budget to accompany our grant application.

When I arrived David was busy in the back of the shop so my ring of the doorbell was answered by partner Richard Lang who ushered me in. As I spread the pages of our book on the conference table I asked, “What did you say your name was?” When he replied, “Richard Lang.” I exclaimed, “You’re RICHARD LANG!!! I’ve always wanted to meet you!”

That was so true—for several years we both had been teaching watercolor classes at UC Santa Cruz and I had seen his course listing in the catalog on the same page as mine. I had often thought it would be helpful to meet a colleague to discuss the ins and outs of Santa Cruz but I had never gotten around to it. To my astonishment there he was, in person. Yes, indeed, “I’ve always wanted to meet you.”

My exclamation certainly got things rolling so after my formal presentation of our project Richard toured me through the facility. On their copy stands and on their computers, I recognized many of the artists they were working with. Although I felt incredibly small, and our book project seemed small compared to the big presses and the big images rolling off the presses, I nevertheless felt an uncanny sense of welcome familiarity.

“You’ve never been there?” Richard asked as we were looking at photos of a beach that were spread on a table. As Richard likes to say his speech bubble says, “I’ll take you there” (thought balloon reads, “I’ll take you there, baby”). “Let’s meet at my studio and we’ll go out to the National Seashore, Point Reyes.” So we made a date. . . and, as the saying goes, the rest is history.

It was intention that brought me there in the first place. It was serendipity that Richard, as it so happened, answered the door. It was Alchemy (the title of our book) that set into motion a magical transformation. Both of us long single and at the fifty-something mark, thinking that we were in the autumn of our lives, too late to start romance again but, we did.

At Kehoe Beach when I bent over to pick up a piece of plastic Richard asked, “Are you going to keep that?” And then he bent over to pick up a piece of plastic and I asked, “Are you going to keep that?” Richard had started collecting plastic at Kehoe Beach in 1996 with his son Eli whose school required community service. They were doing habitat restoration and they found plastic on the beach. So on that day we discovered that we each had since 1996 been picking up plastic on the beach and making artwork out of it. Right away we started collecting plastic together. Since we both were already in the art world, we were invited to collaborate for an environmental art show. From that point we were off and running

Nanette: Talk about your engagement with the process of the beach plastic. Your picking up the plastic and making things. What propels you to continue with this for 23 years, to make things, not just picking it up and putting it in the trash can. It’s not like your picking up litter, it’s like your gleaning art materials.

Judith: We like to say we are curating the beach, not cleaning the beach. On a good day there will be lots of plastic. We were just out for a Coastal Clean Up Day (September 21) and there was hardly any plastic. It is the wrong time of year. They should have it in the winter time.

Nanette: There is more plastic in winter?

Judith: Yes. It comes down the streams and creeks and also the storms and the wind bring more plastic ashore.

Nanette: It’s coming from both directions?

Judith: Yes, it’s coming down and out, and also from the gyre, the currents. But what keeps me going is the thrill of discovery. When you go to the beach you don’t know what you are going to find. For a longtime we didn’t even pick up the wrappers and the transparent plastics. They are almost invisible compared to the bright shiny big chunky things which seem to be the most enticing. But, there are a lot of wrappers. That is a big category of material. For this piece I’m working on [a wedding dress] I am selecting out the transparent from the translucent.

We have big boxes full of brightly colored candy wrappers. This is something that we discarded for a long period of time. Didn’t collect it and didn’t keep it.

Nanette: You just left it on the beach?

Judith: Yes, we left it on the beach.

Nanette: That’s harsh.

Judith: Harsh, indeed! But, we just can’t pick it all up. Lots has been left behind. When it is a really bad day after a storm, there is just no way. Lots is left behind. We can’t pick it all up. We have bags, we have satchels over our shoulders. How much can we really bring back?

We have a routine. From where we park the car it’s about a 20-30 minute walk out to the beach. The trail takes us past a beautiful creek that meanders down to the coast and past a marsh that is home to hundreds of Redwing Blackbirds. In spring bunnies skitter across the trail. It’s a lovely walk. When we get to the beach we always always go to the right and we always collect from a very defined point because we want to make a point about how much plastic two people have collected from this 1000 yards of one beach. To define the parameters as very small makes the measure manageable. We hope that when people hear what we have done, they will say, “Maybe I can do that, too.”

Nanette: It also makes the quantity excessively profound.

Judith: Yes it does. This much plastic is on this one section of beach. Just extrapolate out and think of all of the beaches on the planet. And our beach is not even extraordinary. There are beaches which are far, far, far worse.

What keeps us going is that we don’t know what we are going to find and there is a sense of anticipation, thrill. Sometimes we find something that sparks a reverie, that fits with an earlier piece or completes a project. There is something exciting about being on the hunt.

Nanette: You are hunter gatherers.

Judith: Yes. As a child I aspired to be a paleontologist. Every day after school with friends I would mine the white limestone cliffs in the woods near our house in Dallas. We always hoped to find a dinosaur and spent untold hours excavating a mound where we were certain we would discover a skeleton. We were convinced that the bowl shaped recess in a boulder was an impression left by a dinosaur egg.

We had our imagining but we did in fact unearth many small fragments and crustacean and clam shells. Some 100,000 years ago Dallas Texas was underwater covered by the Western Interior Seaway, and today we worry about sea-level rise?

The Natural History Museum of Dallas has an excellent display of fossils and ammonites from the surrounding area. I would go to look and identify what we were digging up. I would longingly gaze into the specimen vitrines and wish upon wish that someday one of my fossils would be on display with a label attribution that had details about the rarity of the find, the latitude and longitude of the site, notes about the Era, Period, Epoch and yes, across the vast expanse of geological time would be MY name as the collector.

Fast forward some 55 years, I now find myself to be an artist/archeologist mining the beach in search for remnants of plastic, future fossils from the Plasticene.

So in a way, I have become what I had always hope. Because of the things that we find, we frame them as archeological remnants. They are indicators of our consumer culture and they will be around for a long, long time. They really are exemplars of our existence in the same way that the fossils are.

Every single piece tells a story of some kind. A big part of our collaborative practice is writing about what we find and doing research when we get home trying to figure out where the plastic came from, what it originally was. For example, for years we were intermittently finding little red rectangles. We didn’t know what they were. Finally, Richard’s daughter told us that they were the plastic cheese spreaders from Kraft Handi-Snack packs. I am happy to report that this last year Kraft eliminated that piece of plastic and they now have a sturdier cracker or a pretzel which can scoop out the cheese.

Nanette: Do you know what propelled Kraft to do that?

Judith: This is a success story not particularly attributed to us. It is the increasing awareness and pressure around single-use plastics. We did write letters to Kraft and sent them photos, but I think there is an upswell coming at corporations from all sides and they are having to rethink their products. The Handi-Snack individual servings are still in plastic containers and it’s not really food. It is a sort of plastic cheese anyways. Really horrible.

Nanette: With much of the beach plastic work you are taking something that is devastatingly ugly about humanity, our trashing of all life on this planet, and turning it into something of aesthetic regard. . .

Nanette: We get complaints about that all the time. People clamor, “Why do you make the plastic look so beautiful?” I’s trash and people want to be repelled and agitated by it. But, beauty is a great enticement. We move towards it. The shaming and the finger pointing is not motivating. We’ve seen this especially with our prints. It’s like a dance. People will move towards them and say, “It’s so beautiful, the composition and the colors” and then they recognize what it is and recoil back exclaiming. “Oh, my, that’s garbage from the beach.” Then they’ll move forward again, recognizing, “That toothbrush might once have been mine.” It’s in that moment of recognition of maybe “that’s mine” that’s when something will happen.

Nanette: As in they will be more mindful and aware of their use of plastics.

Judith: Yes.

Nanette: You’ve spoken to oil industry executives about beach plastic. Tell us about these experiences and the responses you’ve received.

Judith: Our best story is when we were invited to speak about Citizen Solutions at the Global Philanthropy Forum, a convocation of major funders around issues in philanthropy. Each year it has a specific theme and all the bigwigs come from the Ford Foundation, the MacArthur Foundation, the Skoll Foundation, etc. We were invited to do what’s called a “Spark” because we are considered exemplar: just two people and just 1000 yards of one beach. We were introduced by a guy who was once the Vice President of Chevron but now has a philanthropic position who said, “I’m so happy to be able to introduce Richard and Judith because we are in the same business. We are both mining hydrocarbons.” So when we got on the stage we said, “We are so happy to be here. But, we do feel a little bit out of place. We are the world’s smallest NGO and we are not even that organized.” Everyone laughed, so we did spark it up.

Nanette: Much of the beach plastic work is a collaboration with your partner Richard. Tell us about collaborating and how you perceive the process of collaboration affecting your individual work.

Judith: You do know first hand the difficulties in collaborating. In 1999 Richard and I had just met and right away we were invited to make something for a show. It put a fire under us. We had to figure out how we were going to work together. Prior to that time we each had almost 30 years of independent studio practice. So we were each pretty well set in our protocols of decision making. Joining forces—there were many difficult moments—stomping out of the studio with folded arms—but as we worked it through we developed a lively back and forth.

Nanette: How does that collaboration affect what you do on your own?

Judith: It is wonderful to have a trusted critic who knows me well and knows my way of working, and who can offer valuable suggestions and insights. Richard offers me things that I don’t see in the work. It is also just about the best thing in the world to have somebody who loves and supports your work. In 2004 we were married at Burning Man by temple builder David Best. He surprised us with the simplicity of our vows. He asked me, “Will you help him with his work? Will you bury him?” He asked Richard, “Will you help her with her work? Will you bury her?” That’s it. That is all you really need. To work until you die and someone to help you with both.

Nanette: What was your earlier work like and about?

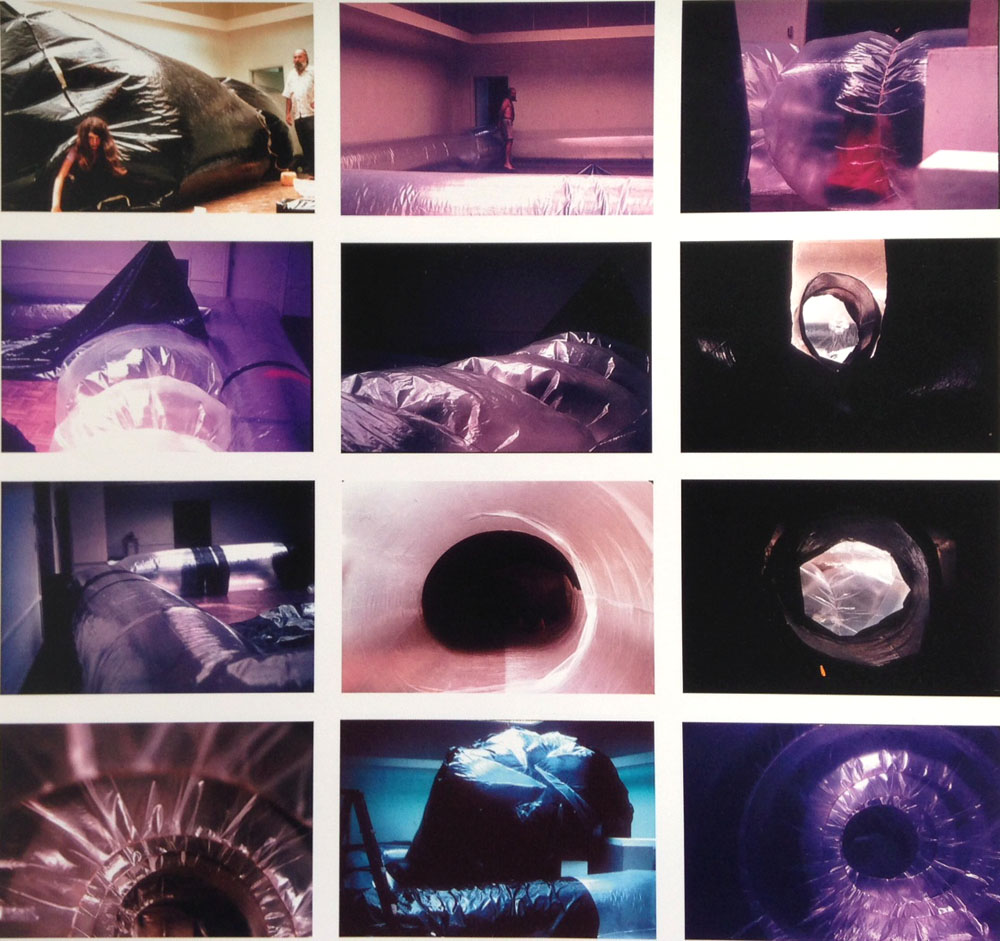

Judith: In the summer of 1970 I took a life-changing class called Environments with Carl Hertel. The class assignment was to use the Lang Art Gallery (no relation) at Scripps College and the material was plastic. In that tumultuous time everything was being called into question and no less in this class. Happenings, experiential theater, sensory explorations were exciting new ways of engaging the art audience.

Carl encouraged us to think big, to think about not only making art but also making the walls, making the whole experience. Carl challenged us as artists to define the container AND the context. Plastic made it possible. It was a lightweight pliable material that with a gentle coaxing could take any shape. So in the gallery we made a multi-sectioned inflatable maze with tube and columns, that people would crawl through.

It was great fun because it was about creating an experience of space in a very different way. We would blow these great big things up in a public park or a plaza and invite the public in.

Nanette: Where they representational?

Judith: Mostly not. They were abstract shapes. I was captivated by the idea of pure experience free from an identifiable or referential form.

Nanette: And they were plastic. Isn’t that interesting. . .

Judith: Yes. It was thin polyethylene sheets of plastic which we would heat seal to put together or sometimes used duct tape. That was in a way, a start.

I want to go back to another significant time in Dallas in elementary school. Our art teacher took us to an exhibition of artists’ books—a papyrus scroll, the Gutenberg Bible, and illustrated manuscripts—the lights were low, it was like walking into a magical sanctuary. Back in the classroom she taught us how to sew bindings and make book covers, and make books. We made a real book. That stayed with me, the love of making books, and has been an ongoing practice. All along this has been a form that I have enjoyed in various permutations—books, book like objects, or sequential experiences of some kind.

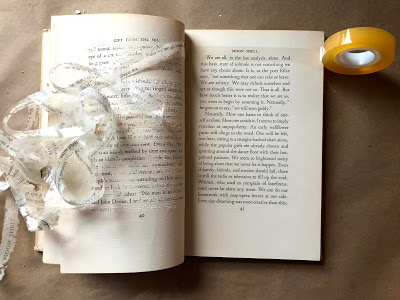

Gift from the Sea is a recently completed book performance project. Making it was my evening activity for a long time. I lifted the words out of this book with cellophane tape, line by line. The text is on the tape, but not all of it is completely visible. This year on my birthday I performed this at Kehoe Beach. I laid the line of text out on the beach and people could walk the line of it and read it, which they actually did. People could dip in and read sections, creating their own poetry as they moved in and out of the piece.

Nanette: Tell us about a typical day in your studio practice.

Judith: I get up early, have a cup of coffee then tend to business. Being an artist is not just about being in the studio. There is a tremendous amount of writing, getting things figured out, communicating back and forth with curators. So I start by clearing the email deck as it were. Then Richard and I review any collaborative projects that we are working on and take care of that business. Then I have studio time until lunch. Richard and I always have lunch together. The afternoon is full of more studio time. Then dinner and maybe watch a movie while I rustle. There is always rustling—knitting or working on plastic or some handiwork. Gardening is also a big part of my practice, so there is digging, planting, watering.

Nanette: What do you find challenging as an artist?

Judith: What to do with all this stuff. Part of my studio time right now is focusing on organizing archives, organizing the beach plastic archives, making a chronology of my/our work. It is important to me to be the caretaker. I feel I have a responsibility to each of the projects and that each has a story to be told.

Nanette: Who inspires you?

Judith: Greta Thunberg. She is an exemplar of the younger generation coming up who will take the banner and run with it. She gives me hope. We could easily fall into despair about how bad things are, and then these bright shining lights come up, and they make us think it will be okay.

Nanette: What question keeps you up at night?

Judith: When I wake up a three in the morning, I read a little bit and then, as I’m drifting back to sleep, my mind goes over and over my running list of things to do. It doesn’t keep me up. I actually feel blessed that I have so much to do and the wherewithal to do it. I have the energy and the time to make headway on that list. It’s crazy because keep thinking of more and more things to do. I am very grateful for this time in my life.

Nanette: Do you think art can change the world?

Judith: That’s a big thing to ask of art but I remember Tom Clark and what Wyeth’s portrait of him did for me and the many others in Dallas who were also touched. I see changes in the plastic world. There is a big international upwelling of people using art to message what is going on. Plastic is washing up on beaches all over the planet and artists are picking it up and making marvelous stuff out of it. That is amazing. That is affecting a change right there. We don’t need to go out and buy more art materials. There are art materials a plenty. We just need to use what we already have and think of inventive ways to use what we have. In that way, the change is amongst us already.

Whirligig interview by Nanette Wylde.

Judith’s websites:

Judith’s work https://judithselbylang.wordpress.com/

Judith’s books https://selbylangbooks.wordpress.com

Jewelry blog http://beachplasticjewelry.blogspot.com/

Beach plastic website http://www.beachplastic.com/

Beach plastic blog http://plasticforever.blogspot.com/

Exhibition blog https://foreverplastic.wordpress.com

About our garden https://ranchodblog.wordpress.com

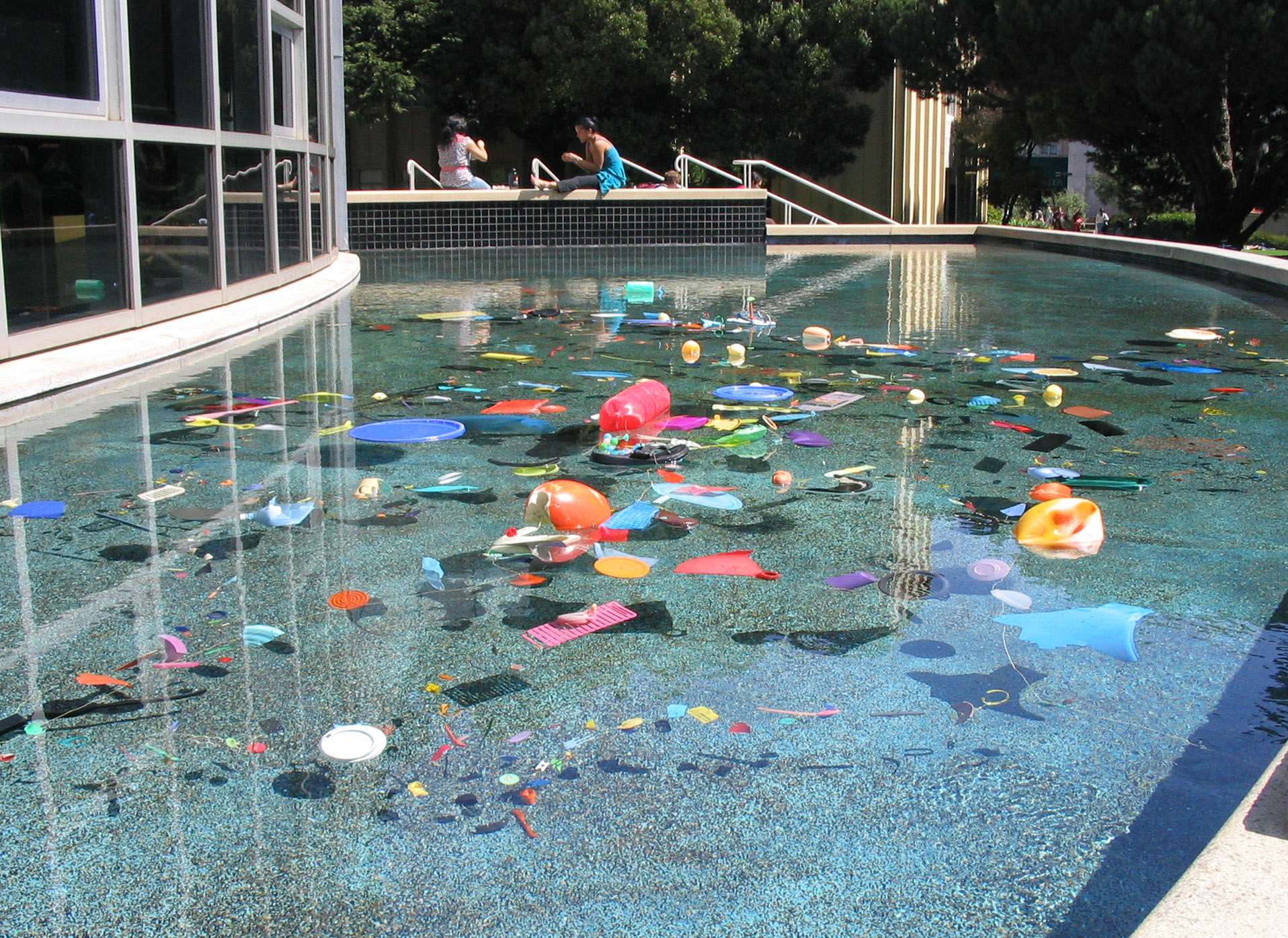

Images from the top: Judith Selby Lang at Kehoe Beach (photo courtesy of Richard Lang); Like Diamonds, Plastic is Forever; Water Lillies; Chroma Red; 4600 in the Reflecting Pool at the Gleason Library in San Francisco; 4600 at the American Visionary Art Museum (photo courtesy of AVAM); Nurdles; Recycle Ryoanji; Early Inflatables; Gifts from the Sea; Gifts from the Sea at Kehoe Beach. All images courtesy and copyright of Judith Selby Lang unless otherwise state.