Photographer and video performance artist Julia Bradshaw is exhibiting seven different series of work in her first one person show at Fresno City College this month. Her work often comments on language and the mixed messages of cross-cultural exchanges.

Photographer and video performance artist Julia Bradshaw is exhibiting seven different series of work in her first one person show at Fresno City College this month. Her work often comments on language and the mixed messages of cross-cultural exchanges.

Bradshaw was born in Manchester, England. She spent nine years working and living in Munich, Germany where she studied with Michael Jochum before coming to California in 1995. She received her MFA from San José State University in 2007. Bradshaw is Assistant Professor of Photography at California State University, Fresno.

Whirligig: At Fresno City College you are exhibiting seven different series of photo-based works: Cut Pieces (2010), Case X (2010), Nocturnal (2010), On Photographing Breasts (2009), Tissue Blowing Project (2007), Constraints (2003), and Companions of my Imagination (1994). What is the thread between these bodies of work?

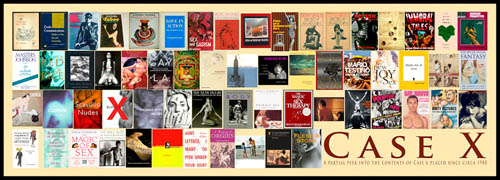

Julia: I am interested in the photographic series as a means to problem solve or comment on everyday life. Apart from the Nocturnal series, all of these projects have something to do with our culture and society. Cut Pieces, On Photographing Breasts and Case X are all linked in that they have to do with my investigations into libraries and books. They consider book content, the public’s misuse of books and a library’s policy on “protecting” books. The Constraints Series has to do with the various societal dictums that potentially have something inherently good and bad associated with them. For example, I have an image and text combination I call “polite conversation.” In this image I am trying to say that “polite conversation” is positive in that it ensures a civil society, however it also has a negative aspect in that polite conversation also can prevent people engaging at a deeper level. Likewise in the Tissue Blowing Project I am also thinking about language. In this project I visually represent miscommunication, disputes, failed advances, diametric viewpoints and avoidance and absence in relationships.

With this exhibition I was very aware that I was exhibiting works in an educational establishment, so, to a certain extent, my role as an educator came forward in the choice of the series in the exhibit. I had three goals as an educator. I wanted students to see the series as an opportunity for photographic exploration. I wanted the viewer to understand that art can be used for social engagement. I wanted to have a discussion about how structure (wall art vs. book art for example) can inform the work.

Whirligig: What is it about working a series that interests you?

Julia: Even now, having worked many years in a serial form, I see my inability to work with the singular image as a personal letdown. This is because an iconic singular image by a photographer communicates its purpose perfectly and evocatively—no words or other images are needed. I am thinking of images such as Edward Weston’s Pepper #30 from 1930, Ansel Adams’ Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico, from 1941 or Nan Goldin’s One Month After Being Battered from 1984. However, as Henri Cartier-Bresson wrote in his Essay “Images la sauvette” 1952 (published in English as “The Decisive Moment”) “. . .Sometimes there is one unique picture whose composition possesses such vigour and richness, and whose content so radiates outward from it, that this single picture is a whole story in itself. But this rarely happens.”

I agree with Cartier-Bresson that this rarely happens. One image might be stronger than the others in a series, but even that image is enhanced by the series as a whole. With the photographic series, no singular image can communicate the whole of the series. The other images are needed to enhance, complement, create diametric viewpoints, reflect and engage with each other. For that reason I am often attracted to the artist’s book as a container for the photographic series. With a book, a viewer understands that all the images are intended to link together in some manner.

Whirligig: Do series continue for you after you think you are done, or are they done when they’re done?

Julia: Generally when I am finished with a series, I am finished with it. I rarely revisit the idea, although I might play with the form of presentation. At some point when I am making a series, it becomes repetitive and more images are not needed. Therefore a series may end at two or three images or contain hundreds. The series and what I am trying to say dictates the number of images.

With the Cut Pieces series, the project could have continued ad nauseam (sadly as it has to do with the violation and mutilation of library books), but in reality how many images does the viewer need to see to “get it?” Â Sometimes circumstances stop a project, for example my Flying Project stopped for two reasons (1) seats started to get too close together in airplanes that my camera was unable to focus automatically and (2) because after September 11, I felt that my photographic activity would no longer be viewed without suspicion. Other series, such as the camping series, I have worked on for over five years now with no end in sight mainly because I am uncertain of the form of the final project.

Whirligig:Â Some of your work takes book form; and other times it derives content from existing books. What has been the influence of the book in your life, or where does bookness carry importance or significance for you?

Julia: I distinctly remember getting my first book as a Christmas present when I was about eight years-old and rationing the short stories so I could make the book last longer. That didn’t work. I read the book within a couple of days. My mother took us to the local library weekly, so I have always read a lot of books and have always used the library regularly wherever I have lived. However, growing-up, there were very few books at home. My parents’ very small bookcase was filled with maps and guide-books and a handful of classics such as Dickens’ David Copperfield.

Today I am an avid reader and borrow books from the library avariciously during vacation. I read probably 20 fiction books during the summer holidays. I panic if I do not have anything to read.

If I buy a photography book, I prefer not to collect compendiums or retrospectives of photographers but books that have a completeness about them; where the photographer has thought about image-order, sequencing and where the book is the resolution of a comprehensive idea. The concept of “bookness” where image order matters, where the relationship of one image to another matters and where the artist clearly has an input into how the book is assembled is very interesting to me. Just recently a book was published about the making of Robert Frank’s book The Americans. This is a fascinating read and covers the complexities of image sequencing and the assembling of the book.

Whirligig: What is the significance of the library to your work?

Julia: I like to spend my free time sitting in the stacks and looking at books. I like the surprise of the library. I might go to pick up one book by a particular author but then the adjacent book catches my eye and I am lost.

Attitudes and tastes have changed over the years, and the library is often a depository of those tastes. Sometimes it is useful to revisit older books in libraries to discover where we have come from and consider how the representation of ideas has changed over time. I also firmly believe that a library is representative of the cultural tastes of an institution. For the Case X piece, in which I am drawing attention to a segregation of certain books in a library’s collection, I even researched the library’s intellectual freedom and collections policies to ensure that my pointed criticism was based in good practices.

Whirligig: What are some of the difficulties and problems you have experienced in doing library-based work?

Julia: I had no problem doing the work. However, with the Case X piece, I am actively trying to get the Case X books returned to the general stacks, so I have shown the work to the library’s management. Making art that can be interpreted as a form of social activism is new to me.

Whirligig: You employ a lot of different types of media in your work and much of it is media that has historically served reproduction purposes—letterpress printing, screen printing, digital imaging, photography, books, video—talk about your selection of media for different projects and whether the choice of media derives because the media serves a particular idea or because you are interested in exploring the media for its own sake.

Julia: Regarding the reproducibility of my chosen media: I am interested in the democracy of a medium—an artwork that can be reproduced is theoretically available to many, many people. To a certain extent it is non-elitist, which appeals to me. Because of this, I rarely create limited editions my works. If I was taken up by a gallery, I would have to reconsider that issue but at the moment, what is left of the Marxist in me embraces these media for the ease of distribution and accessibility.

I also believe there is the perfect medium for each idea and as I am introduced to new forms of media, new ideas develop because of the possibilities of that media. I firmly believe that ideas can evolve because of a thorough understanding of the medium’s properties. For example, when using film in photography, there is a numerical progression of the images you have taken (e.g. 1,2,3; 36 for 35 mm film) and that numerical progression can be used to develop project ideas. This is the case in the As the Earth Turns project: in these images, my body represents the gnomon in a sundial and thus the numerical progression of the negative strip enhances and informs the concept of time passing.

I also sometimes choose to work with a medium simply because I enjoy doing so. Particularly with photography’s transition to digital media I occasionally choose to make images using traditional processes or in the darkroom because I enjoy using my hands. The Nocturnal series of images are traditional silver-gelatin images and I believe that they have a greater presence in terms of the quality of the images than black and white digital prints. As the purpose of these images is to communicate something metaphorical, that the images have a greater presence in terms of the medium is important to me.

For the same reason I also learned printmaking with Kent Manske at Foothill College. In taking printmaking classes I was less interested in making a finished product than in engaging in the creative process. As I am never certain of the form my projects need, having knowledge of many different forms of media informs my work.

Making books also involves using my hands and I was very fortunate to have been introduced to the art of bookmaking when I lived in Germany. I continued my investigation into bookbinding in this country and in particular worked with Don Drake of Dreaming Mind Bindery to refine my skills. As I am only interested in making books using the photographic series, rather than about the book-object itself, I do not expect I will ever become expert with this medium. However as I said before, the book is a wonderful container for a series of images. In using the book as a form I can control pacing, reversals, image combinations and juxtapositions to control the viewers’ engagement with my work.

In terms of video, I use it because people will watch a video for minutes, whereas they will engage with a photograph for maybe 5 seconds. I’m just being pragmatic. If I want to get my idea across, keeping the audience captive is helpful!

Whirligig: How would you categorize or define your own work?

Julia: I am an ideas-based art maker. Because of that it is hard to categorize my work although most of my works contain lens-based media at this point. I generally say that I create artworks as a means to problem solve or comment upon issues of the everyday; such as social interactions, language or being an artist. I am always surprised by the wry humor in my artworks, I never deliberately start a project with that as an intention.

Whirligig: Is there a particular experience you want to achieve for your audience?

Julia: I want to make my audience think. I want my audience to know that photography and art making can be used to start conversations about our interactions in our world and how we interact with it.

Julia: I want to make my audience think. I want my audience to know that photography and art making can be used to start conversations about our interactions in our world and how we interact with it.

Whirligig: How does the conceptual play into your processes?

Julia: The conceptual plays a huge part in my approach to art making. In making artworks I want to make art that will make me think and I use art to help me work through an idea. It is always the idea that drives the artwork. I used to also believe in the traditional view of conceptual art that the idea takes precedence over aesthetic concerns. However, in this media-saturated world, I now believe that both the aesthetic and the idea are important. I also believe this is a feminist issue—women have to show greater technical skills to be taken seriously as artists’but this is not something I have seriously researched. For this reason the term “conceptual” and how its meaning has evolved in art historical terms is problematic in some ways.

Whirligig: How does the artist/creator come to select a particular approach to making; or what plays into your decisions regarding how to actualize a concept/project?

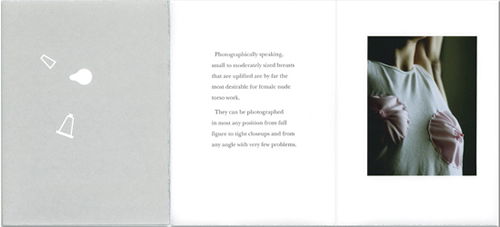

Julia: This varies from artist to artist. I never know when my ideas will come to me. I think this is why I constantly put myself in new situations—I want to see what will happen and what I will think about. Sometimes I think about an idea for years before I act on it. Other times, On Photographing Breasts, for example, the idea came a few years before but it was only through the collaborative process at PreNeo Press that the form of the idea was developed. If I don’t think the artwork is necessary, I often don’t do it. I am not a huge fan of making art for the sake of making art. I am very purpose driven in this respect.

Whirligig: How did you come to be an artist? and specifically a photographer?

Julia: I always envy the people who knew from childhood that they wanted to be an artist and who have a studio practice that involves working in the studio. I came late to art making and probably did not enter an art gallery until my mid-twenties. Although I have owned a camera since I was about 7 years old, deciding to take up photography seriously was a deliberate decision when I was about 25. A decision to have more creativity in my life and also a venue to express my ideas. I started by taking an adult-education photography course at the Volkshochschule in Munich, Germany. I stayed with this group (which functioned more like an intense critique group, than a course) under Michael Jochum for about five years. Initially, it was a struggle finding my own voice as an artist. There are so many expectations of what “art” or “photography” looks like that it makes it difficult for a young, unformed person to develop their own art ideas. It took three or four years of regular photographic practice before I had my first break-through. At that point, I started to make art about my ideas instead of merely representing photographically what was in front of me. After that it was a long and informal process to develop as an artist—a mix of workshops and working with volunteer groups such as the South Bay Area Women’s Caucus of the Arts and the Bay Area Book Artists to form my arts community. Eventually, I made the decision to get my MFA at San José State in an attempt to professionalize my arts practice.

Whirligig: What personal transformations occurred as a result of graduate school?

Julia: I was definitely transformed. Before entering the program, I was happy with my ideas, however I felt that how my artworks were made (in terms of craftsmanship and presentation) detracted from the strength of the ideas. Graduate school gave me the space and time to develop both my conceptual ideas and my skills. In addition, the program at San José State also offered the opportunity to learn to be a teacher. I had not considered that as a career path.

Whirligig: You are in your third year as a Professor at California State University, Fresno. Talk about the challenges of teaching and learning at the university level.

Whirligig: You are in your third year as a Professor at California State University, Fresno. Talk about the challenges of teaching and learning at the university level.

Julia: I think in the third year, assignment plans and teaching confidence merge. I am also more aware of how the academic system “works” so I can get certain things done faster. I am now able to focus on how to make the photography program better and how to help students get the necessary results instead of merely working on the nuts and bolts of class preparation and administration. The benefits are that I have a stable and engaging job in a creative arts field and that I have the opportunity to help bring interesting art to the awareness of students in Fresno.

One of the interesting factors in teaching at the university level is the need to help students transition from being a student to professionalizing their arts practice. I think that most students are only thinking short-term—the next grade or the next assignment—and not always thinking about developing as a professional being, with all that that entails. This is my next challenge; to greater assist students become more independent as artists.

Personal challenges had to do with loneliness initially. In moving to Fresno I lost contact with a valuable arts community in San José. But two years in, I am very happy with our decision to move here.

Whirligig: You were a key figure behind the inception of a major arts festival, the Book Arts Jam, and in fact organized the first two Book Arts Jams at Foothill College in 2001 and 2002. Can you talk about these experiences: how the Jam came about and how your involvement with it has affected you personally?

Julia: I remember Kent Manske, Jone Manoogian, Barbara Mortkowitz and myself meeting at the cafeteria at Foothill College and discussing our dreams and ideas for BABA (the Bay Area Book Artists). I know I did suggest a fair—but I am sure that Kent Manske planted the seed. What I wanted was to give book artists, who do not always have traditional venues to exhibit their work, an opportunity to show and share their work. These artists would be curated into the fair partly to ensure persity of book types, but also to set a level for the quality of the work. As the organizer of the first two Jams, I worked extremely hard to get the word out about the Jam and to personally approach artists so that they would show their work. The fair was never intended to be a commercial venture, but rather an arts sharing venue. An exhibitor did not have to sell work, for example. Now in its ninth year, the Jam has since evolved to include an exhibition, workshops and other public events.

I volunteer a lot for arts organizations. I started doing this before I had my work-permit in this country. Through volunteering I work with people more intensely than I would in other more casual social situations. It is my way of developing my arts community and I value tremendously the support of people I met through these volunteer organizations. People such as Kent Manske, Jone Manoogian, M.J. Orcutt and Jade Bradbury were all instrumental in encouraging me to go to graduate school and in encouraging me to become the artist I am today. Now I am heavily involved with the professional organization The Society for Photographic Educators and also the Council of 100 at the Fresno Art Museum.

Whirligig: How do your activities in creative communities such as writing for Art Shift and collaborations with art organizations such as Bay Area Book Artists and San José State’s CADRE, inform your own art practice?

Julia: Artshift helped me gain confidence as a writer. My writing has more fluidity because of this involvement and I have since had reviews and articles published on the National level. Writing a review or a blog post is a way of focusing the mind on the art presented. It is too easy to drift through an art exhibition and writing focuses the mind wonderfully.

At San Jos´ State I always felt that the CADRE artists were some of the most conceptual in their approach to art making. I never wanted to join them in terms of media, but getting involved in CADRE, ZER01 and also the Climate Clock Initiative stretched my mind and helped create my bonds with the arts community in San Jos´.

In general, I join groups or work with people who are going to stretch and challenge me as an artist. As I am never sure where or when my next art idea is going to come from, being able to bounce ideas off other people and constantly think about art is energizing for me.

Whirligig: What type of experiences are you looking for as a cultural consumer?

Julia: To be transformed.

Whirligig interview by Nanette Wylde.

Julia’s Website: juliabradshaw.com

Images from the top: Portrait of Julia, Tissue Blowing Project, Cut Pieces: installation view, Cut Pieces: Youdelman, Case X, Constraints: Identity, On Photographing Breasts, Camping Project, Exhibition View at Fresno City College. Courtesy of and copyright of Julia Bradshaw.