Kent Manske is a visual artist working in traditional and hybrid forms of print media. He is a professor of art at Foothill College where he teaches graphic design, printmaking and books as art. His MFA is from The School of the Art Institute of Chicago. This interview was conducted upon the publication of a book on Kent’s work titled Re:ad.

Whirligig: Why do you make things?

Kent: To make sense of things I don’t understand, like my feelings about humanity. I’m compelled to process matters of our existence, like why we believe what we do. I make things to find my own peace, even though much of what I explore is not peaceful. Sixteen thousand people die per day of hunger related causes. The Arctic is melting and the oceans are rising. Exploring issues and concerns help me recontextualize my own reality and make sure I’m not living in a total state of deception. Art helps me to take responsibility for the privileges I’ve inherited.

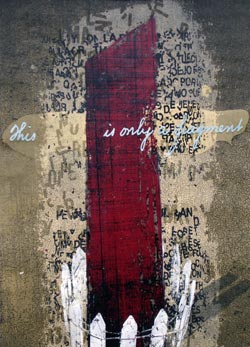

I find joy in the process of bringing ideas from the invisible internal world to the external visible world. The act of making things fuels the investigation and prompts the conversation. It makes learning a focused priority. Being in the studio is about responding, there’s an immediacy, an encouragement to keep digging, to ask harder questions. Printmaking methods serve both the conceptual development of my ideas and the production of finished work. Work produced become maps or guides to encourage additional thought and investigation.

I think the need to express is also a component of why I make things.

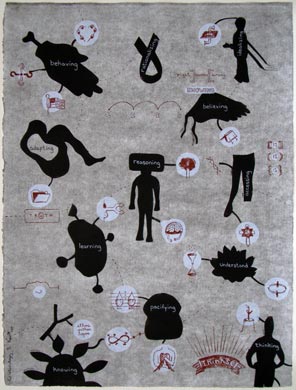

Whirligig: You have developed a vocabulary of symbols. Can you talk about the symbolism in your imagery?

Kent: I create symbols to process the ideas that occupy my thinking. I process questions. I process concerns. I process ideas and wonder. I process the many things that I find interesting that require additional inquiry to understand them. I believe I do this partially out of need to understand how the world operates, and to help me navigate the complexities of it all. Some people can do this by thinking, reflecting. I find that making a symbolic tool as a visual representation satisfies and becomes a map for the exploration of thought. I return to the resulting symbols for both inspiration and continued investigation.

Whirligig: Many of your symbols repeat and reappear over the years in several different bodies of your work.

Kent: Yes. Each symbol evolves with time. I understand it differently when I revisit it. Its meaning expands when I see it in juxtaposition with other symbols. This is partially what brings me pleasure in creating in a visual language. It’s constantly evolving. That is, both the language of the symbols and my relationships to them.

Whirligig: Is there a particular symbol that you are fond of?

Kent: There are degrees to which a symbol has an embedded importance based on history and significance. Symbols representing sensitive or meaningful experiences for me will always retain a connection to that memory. These often occur alongside more current symbols and bridge expanses of time and thought. Although I could identify particular symbols, there are a good handful that represent specific moments in my personal evolution and growth and thus have become spiritual entities for me.

Whirligig: Why did you create a book about your art?

Kent: To learn. I’ve been making images for close to a quarter century. I felt the need to ask deeper questions beyond the images on my studio wall, beyond the tape in my head. To look at everything from a tall ladder. To see if perhaps I need to find a new part in the play.

Whirligig: What did you see?

Kent: The work is more than I am at any given time. Writing about it has helped me wrap my head around it in a different, more explanatory way.

Whirligig: What prompted you to start writing about your images?

Kent: I first started writing about my work in 1996. After slide talks, people would share how valuable it was to hear about the artist’s intentions. I make images because it is a very natural and satisfying way for me to process thought. Thinking alone seems incomplete, fleeting. Words seem overly definitive. Writing is very difficult for me. Although I struggle, I took on this writing project believing it would help me to understand why I do what I do on a different level. It’s about something I read on a well in Kyoto, “I learn only to be content.o” Robert Thurman said, “Life is for education, it opens your brain and heart.” Both of these resonate with me.

When writing about a specific work I’m reflecting on what I was addressing while making it and what it became. I’m not attempting to explain the work or extend the meaning, but instead process and record my intentions.

Whirligig: But aren’t you imposing meaning?

Kent: Yes. Do the meanings change for me as a result of fixing a set of words on them? Yes. Is this a bad thing? If I felt so I would likely have abandoned the writing idea earlier. It was a decision I felt would produce stronger work in the end. Time will tell.

Whirligig: You are the middle of five boys raised in a suburb of Milwaukee. What was your childhood like?

Kent: We were raised strict. We were encouraged to participate in things. We went to church every sunday and as long as you lived under their roof you had to do that. Things were regimented. It was a system that defined what family was. These things were controlled by mother and father. Each had their specific roles and they rarely stepped on each other’s territory. Mom managed the house. Dad managed the affairs. Brothers had interest in each other, but had independent outside acquaintances. We went on camping trips twice a year, generally a road trip to another region of the country. On the agenda were historical sites, national parks, souvenir shops for mom.

Whirligig: Were you encouraged to be creative as a kid?

Kent: In many ways I was taught to solve my own problems, to look it up, to fix it, to figure it out. I think my folks were teaching us survival skills, not just coping with five boys. They required us to be scouts and play a musical instrument. I’m now thankful for this and all the museums and historical sites they dragged us to. I think I rearranged my bedroom every week. Which I regarded as a creative act.

Whirligig: What is your single most favorite memory of your childhood?

Kent: Either I don’t have a good memory or childhood was pretty pedestrian.

Whirligig: Did you have any frightening experiences as a child?

Kent: When I was probably seven or eight years old, I had nightmares that dead people occupied my mattress.

Whirligig: Did you ever figure out the source of that?

Kent: No, it just went away. But I recall both of my parents consoling me.

[Another was] losing control of my bike going down a steep hill with someone on the back, illegally. I lost control and I’ll never forget that fear. I was eleven. I lied to my parents about the injury I got and they figured it out because my bike was damaged.

Whirligig: Five boys. Was it a competitive environment or ?

Kent: Yes, but not encouraged. We were encouraged to work together. Competition was a healthy and natural way for advancing our skills in sports, scouts.

Whirligig: How has your conservative religious upbringing influenced your adult life and your art work?

Kent: It has shown up as iconography for decades as part of an exploration of expectations. Being one who tries to please it has always affected me that I didn’t fulfill my parents wishes for lifestyle and belief. I spent a good amount of time in my work processing whether it was OK, right or wrong, questioning what my responsibilities were. These questions helped me pave my own path, quest and independence. I think that processing was rooted in being taught strong family ties particularly through the example of my parents honoring their parents by continuing traditions and behaviors, many of which I now find irrational and uncomfortable. Not the way I choose to live in the world. I have limited patience for following norms based on expectations or traditions.

Whirligig: Do you think that’s because of the upbringing or because of the processing of the upbringing?

Kent: Clearly the processing of the upbringing.

Whirligig: You had music lessons as a child and music is now very important in your daily experience. Did you and your brothers or friends have a band?

Kent: My chosen instrument was the guitar. My first encounter with the guitar was performing as one of the Monkeys with cardboard and wooden fake instruments. We performed in the garage where we kept the record player in the boat and fooled the neighbor kids that we were the Monkeys. I recall it being quite a high.

My father bought me a guitar and my mother took me to lessons. We performed as a group of students songs like “This land is your land.” (laughs) My father didn’t play the guitar but I remember him trying to teach me new chords. This was one of my hardest experiences as a kid because I recall not wanting to learn it because it was too hard and my father being persistent. What hurt me as much as not being able to do it was disappointing him.

I eventually dropped the guitar and picked up the trumpet. I played in the band from 6th through 10th grade. In 11th grade I joined the choir. I was always 2nd or 3rd chair as a trumpet player and I knew I would never be first chair because I didn’t practice like Bob Meyer did. I was pretty much forced to join competitions for medals by both the band director and my parents, and went to every judging knowing I was unprepared. But oddly enough I was proud of those medals like I was proud of swimming ribbons that were sometimes not really earned but were given as consolation prizes.

The highlight of my music training was 7th grad jazz band. Director John Monger dressed this small band in paisley shirts with fake turtlenecks and it was fun. I wish that I didn’t let the social stigma of being in a band interfere with being proud of being in the band. I guess I’m recalling peer pressure that band was for losers.

Whirligig: What is your earliest memory of ‘art’?

Kent: Probably on vacations going to blacksmith shops and guild displays and liking the totality of the making that was observed. My earliest self-fulfilled art project was a batik I did where I made a soft sculpture like Claes Oldenburg, of a King Edwards cigar matchbook. And the reward of being acknowledged for taking a project into another realm, not just doing a batik but making a sculpture out of if. I particularly recall my mother volunteering to do the sewing. Unfortunately the piece rotted in the garage.

Whirligig: Did you go to art museums and exhibitions?

Kent: No. Generally historical and craft museums. But we took family field trips to the local museums and that included the art museum and the library. I remember a particular trip to the library. I thought it was the dumbest thing ever. My mom told me just to go wander. I went to the animal section because in 6th and 7th grade that was my favorite thing to study. I recall really enjoying the library but being afraid to tell my parents, so I probably pretended it was still dumb, but i really thought it was pretty cool. Now as an adult and reflecting on these things it is interesting to note that I resisted the things that most turn me on today.

I do recall returning to the art museum with my parents after two semesters of art history in college and feeling very proud to educate them why these works were important. Also in high school, art was one of my chosen electives. I remember loving the projects, but having zero interest in the history. In fact, I failed the art history test because I was more interested in rebelliously communicating to the instructor that it was all bullshit and totally missing the lesson. It wasn’t until I was in college that I learned Virginia Driscoll was regarded as one of the top high school art instructors in the state.

Whirligig: You seem to have had quite a rebellious streak as a teenager. Do you know what that was about?

Kent: I was a troubled teenager. Not knowing who I was or where I belonged. I was regarded as a friend to everyone because I shared interests in the jocks and the freaks. I was one of the few people comfortable navigating the two terrains. So there was often confusion about where I belonged. My escape in high school from needing to make those decisions was to hang around with more isolated people. I worked a lot, smoked pot, and retreated to my bedroom to listen to music.

Whirligig: Who really turned you on to art?

Kent: Paul McCoy, 1979, Art Appreciation class. Long gray ponytail, jiggled his keys in his right pants pocket. He was excited about every lecture. John McDermott, 1985, Philosophy of Literature class and another in Postmodernism. They showed me that a life committed to thought produced both an engaged existence and the potential of endless inquiry. Both intrigued me.Â

Whirligig: You started your creative professional life as a graphic designer. Why/How did you make the transformation to fine art?

Kent: My undergraduate was in advertising design and visual communication with an art minor. I left undergraduate with a strong portfolio which allowed me to enter the work force as a designer. I shortly found that my evenings and weekends were occupied with my personal artwork. Six years after my undergrad degree it was clear that I wanted my life to revolve around my own work. That’s when I left design and went to graduate school. I built a portfolio specifically to get into good schools. I like the responsibility and discipline of graphic design, in other words, designing to solve other people’s communication problems, but I like the vehicle of my personal art to express my politics. My fine art at that time was dealing with social, environmental and political issues.

Whirligig: Do you think it’s not now?

Kent: When I went to graduate school it became more about personal symbolism rather than overtly political.

Whirligig: So you became less obvious in your agenda?

Kent: Yes, less obvious, less direct.

Whirligig: And then you became a teacher . . .

Kent: Yes, and remain a lifetime student. There is so much fuel to be creative around us. Life begs our participation. Helping people to express themselves is a joy.Â

Whirligig: What do you like about teaching?

Kent: The learning part and the art part. Helping people develop skills for critical thinking, observation, reflection and inquiry. Encouraging an appreciation of the world, from the preciousness of a spider’s life to the unfixed nature of existence. I also really enjoy helping people develop craft and an appreciation for what it takes to make something not only smart, but beautifully made.

Art is an investigation of being. Possibilities are revealed and break the mold of obviousness in life. Art is an exchange and offering. It presents insights that transcend things commonly known. It presents reasoning that doesn’t have to claim definitiveness, it doesn’t have to be right or rational. Art feels good and is survival enhancing.

Education encourages an engaged citizenry. Richard Florida, in his book “The Rise of the Creative Class” talks about the opportunity for people to turn their soul searching into action for social renewal and transformation. I try to steer students towards careers and practices that enhance community.

Whirligig: Can you talk about your process?

Kent: Talking process can be answered two ways. One, describing media and the other evolving ideas. Ideas: making things visual helps me process in ways that other people can do just by thinking, but I think most personally satisfying is the act of generating product. So making things advances dialogue that is important to me personally, spiritually, psychologically and politically. In some regards it helps me sort how I’m feeling, helps me sort and organize concerns.

This is satisfying in several ways including just the shear act of being creative and coming to resolution with issues that may not have gotten resolved unless I had this vehicle of making. My process of evolving ideas is about questioning and inquiring. The art product is the residue of that investigation. That always doesn’t seek an answer but seeks a fulfillment in the thought process and if that doesn’t happen the work is often abandoned out of just exhausting itself.

Whirligig: How does your brain process information?

Kent: All over the map. I have real challenges bringing order to things. I think I have to work much harder than other people at linear tasks. I think I’ve always disciplined myself to work hard at difficult tasks. Sometimes taking them on to prove things to myself. So sometimes it takes me an enormous amount of time figuring out how to do something just to accomplish it, but it’s this discipline that brings satisfaction. An example of this would be writing a letter to a group of people. It takes an enormous amount of time because there is certain criteria for it to be right before I can let it go. That same thing happens with many of my art objects. There are a lot of criteria before they are right.

Whirligig: Are these criteria self imposed.

Kent: Very.

Whirligig: Do you know what they are specifically or is it more of an intuitive feeling, the rightness of things?

Kent: The rightness is intuitive, but for linear tasks or organizational tasks that have a public face to them much of their criteria is based on a concern for how the effort will be perceived.

Whirligig: The effort or the effect?

Kent: Both. The effect because the ultimate goal is an objective. The effort because I am quite conscious of not wanting to be perceived as a flake or as irresponsible. I have quite a high standard for myself in these regards.

For my non-linear artistic endeavors, the criteria is less about a public face and more about the integrity of the finished product itself. What we talked about earlier, its rightness, and those qualities include intentionality, resonance . . .

Whirligig: Do you think this is related to your dyslexia?

Kent: I do. I think I’m trying to overcome handicaps. Proving to myself that I can do something. I like raising the bar. Doing something better each time. I take great pride in constantly growing and improving. I also think the need to have things organized has to do with the dyslexia also. When I’m not organized I feel out of control and that is uncomfortable, yet I relish in certain amounts of chaos as it seems to feed the adventure. That includes waiting to the last minute to get things done — collecting too much information and then not being able to retrieve it.

Whirligig: What experience do you want people to have with your work?

Kent: I would like people to be provoked by the multitude of readings that can take place. I would like people to have a personal experience interpreting, digesting, using their imagination: why this thing exists. What inquiry it prompts and perhaps what significance it brings to the time and place that we’re in. I have to admit that I feel unrewarded by the lack of investment given to my work. I don’t dwell on that disappointment but instead I think it fuels me to make connections and relationships that are even more complex and more individual. Because that is really what rewards me most. As example, decisions I’m making now in my work are referencing codes and histories of many other bodies of work, and these kinds of connections would be impossible for the audience to decipher. Therefore it would be silly for me to expect that level of reading. So I am processing now more than I have in years that the visual record is clearly my own universe, and that actually provides me with my own little secrets and it’s kind of turning me on. My own secret language.

Whirligig: I’m a bit confused because earlier you said that you make work to understand processing and the product is the residue. Now you have said that you have been disappointed by people not being able to read that residue.Â

Kent: My disappointment that I spoke of is less about others reading my intentionality. I’m observing very little investment in reading at all. More surface reading. My works are not inciting the type of conversation that I would like to have with people.

Whirligig: Are you speaking generally or specifically about your artwork?

Kent: I think this is generally. I hope for more visual literacy in most people I discuss art with. And because I enjoy getting feedback on my own work perhaps I’m expressing disappointment at the level of critical reading.

Whirligig: How has your work changed over the years?

Kent: Because the work is cumulative it’s imbued much more with a larger language and discourse. I am enjoying developing a visual language, so the work seems to me to be richer and richer in behind the scenes stuff. The work is heavier, more loaded and I guess I know this because decisions I’m making are about that development and evolution rather than repeating style or repeating technique. The works are trying to invent new ways of coming to fruition based on previous investment. This also keeps it, for me, fresh.

Whirligig: What do you appreciate in other people’s art?

Kent: I appreciate works that teach me something. That educate me in another way of seeing things. The whole language of art is so much more holistic than written language or spoken language. I like an artist’s work that resonates a sense of inquiry, a sense of ambiguity, and things that reveal themselves that are new. New ways to think, to feel, to process, to help understand what we don’t already know or to better understand what we think we know. I like work that provokes. I like work that breaks language barriers. In other words the ability to transcend language in ways of communicating ideas using methodologies, techniques and style that are fresh. I create to see things more clearly and work by other artists that help me to see with fresh eyes is really a gift.

Whirligig: I understand you garden as well.

Kent: I find the world a little bit overwhelming and certain practices help ground me. That includes gardening, making things other than art. Making food. Gardening provides connection to the physical earth, to the cyclical earth in ways that contemporary existence encourages one to forget about.

Whirligig: What makes you angry?

Kent: My own limitations. My inability to deal with my limitations. When my inability to deal with my limitations are seen by other people. That last one would be more of a disappointment than anger. I am angry at people who behave in ways that are unethical, self-serving, and not inclusive. I am angry at my government. But maybe its not anger. It’s disappointment. Where I become angry is when I see the hurt that is the result of unjust actions. But I’d say most of my anger is self-criticism. I’m angry at myself a lot.

Whirligig: Is this a judgment issue?

Kent: Yeah. And it generally revolves around having expectations. Expectations to being able to accomplish something without effort. Expectations that I should be able to do these things without having to work so hard.

I’ve been told that I’m quite critical. One thing I know is that I’m very critical of myself.

I had to work really hard just to pass high school. To this day I’m still working really hard to keep up with my profession.

Whirligig: What is the hardest lesson you’ve had to learn?

Kent: I recently lost my dog and was unaware that her condition was physical and I pushed her to do things, little things like go on walks. The lesson was not listening. It hurts me to this day that I caused her some suffering that wasn’t necessary by having expectations that she should be healthy and still go on walks. I like to use these [lessons] as opportunities to grow.

Whirligig: What do you do for relaxation?

Kent: Swim. Read. Garden. Follow clues from my wife to do things like go to movies.

Whirligig: Do you have a favorite author?

Kent: I generally choose books from a pile that my wife has encouraged me to read. I rarely read the same author twice.

Whirligig: What do you hope people will get from reading this interview?

Kent: I hope that it will encourage people to think critically when looking at art and to dig deep inside to find out what it means to them.

Kent’s website

Re:ad, Kent’s book project page

Whirligig Interview with Kent Manske conducted by Eileen McGarvey and Nanette Wylde.