Jane Reichhold is an internationally recognized and award-winning artist and poet, prolific writer, editor, publisher, and scholar based in Gualala, California. Jane has written thousands of poems and published nearly 35 books on haiku, tanka, and renga, including Basho: The Complete Haiku (2008); Ten Years Haikujane (2008); and Writing and Enjoying Haiku: A Hands on Guide (2002). Jane is a co-editor of LYNX, the publisher of AHA Books, and editor of AHA! POETRY where she keeps the practice of writing successful haiku and other Japanese poetry forms alive and lively.

Whirligig: You spent over twenty years working on Basho: The Complete Haiku. What compelled you to create this book? Can you talk about your motivations and processes?

Jane: I felt that if I could really see how Basho wrote his hokku, by seeing each word he used and not some translator’s idea of what a haiku could be in English, I could figure out how to write a better haiku. I started first by collecting every translation of each of his poems and comparing them. Then I asked Japanese friends to give me a word-for-word translation. I began to study Japanese but still depended on Japanese translators. My only contribution was to understand how Japanese poetry works and to make the translations fit or follow these precepts.

Whirligig: That’s a very humble response for twenty years of work which resulted in invaluable insights for both Basho and haiku scholars and enthusiasts.

Jane: Truth, like haiku, is so simple.

Whirligig: What initially drew you to haiku?

Jane: On the sale table at City Lights Books Store in San Francisco, in 1968, I found a Peter Pauper book of translations for a quarter. Though I had been writing poetry since college, I felt that here in the Japanese poems was a new way of expressing poetry. Soon afterwards I was making a vessel on a potter’s wheel and just as I pulled the clay upward a bird sang out. I had the feeling that it was the bird’s voice that caused the clay to rise. I realized that in this coincidence what I felt was the same kind of inspiration Japanese poets valued.

Whirligig: Did you write a haiku about that realization or about the rising clay and the bird?

Jane: I have tried. Every few years I try again. I have never gotten a haiku that contains all I felt and still feel about the experience. The only thing these less-than-perfect haiku have accomplished for me is to keep alive the memory of that moment for me.

Whirligig: What is a “haiku moment”?

Jane: A moment of inspiration that is then expressed in a haiku. In the 1980s it was taught that only haiku written about such a moment of inspiration that occurred in the natural world were worthy of the name haiku. It was also implied that if one’s “haiku moment” was true enough, an excellent haiku would result. Later it was acknowledged that writing skills were necessary and could be taught. Still I have to admit that certain moments of insight—those showing an association, contrast, or comparison of things ask to be written into haiku and rarely in any other poetry form.

Whirligig: Can you explain the difference between the Japanese conception of sound units and English syllables?

Jane: The simple answer is that what the Japanese are counting to form their poems (kana) are much shorter than English syllables. A kana is most often a vowel plus a consonant (ka, ke, ki, ko, ku,) but very often just a vowel or a consonant. When we use 17 English syllables we have about one-third more information in the poem than the Japanese do. It is much like trying to build two towers the same height out of the same number of bricks of different sizes. Because the numbers of the parts of the haiku (5,7,5) are so ingrained in Japanese thinking, it has taken some time for those teachers to realize how different our languages are and to allow writers the freedom of pursuing brevity and clearness instead of counts.

Whirligig: What makes a haiku successful?

Jane: When a reader is able to take in the few words of an author to build enough images to follow the wonder, miracle, or insight to make his or her own poem. The reader’s delight, or not, determines whether the poem is successful. If the reader can find and create poetry out of a minimum of words then the haiku is a success. It always takes two to make poetry—the inspired writer and the informed reader.

Whirligig: How is this similar or different from the success of western or contemporary poetry forms?

Jane: Western poetry most often involves the author telling the reader what he or she did, thought, or what he or she wants the reader to think or believe. Haiku just state an observation, at best stripped of author and judgments, in enough words so two or three relevant images can form in the reader’s recognition that are rich enough to create the poem.

Whirligig: This makes me think of some of the stereotypical impressions of differences between Japanese and American culture, with haiku being observant, reflective and aware; and Western poetry being self-involved and agenda-driven. What do you think? Is haiku a more evolved and elegant form?

Jane: I do not think of haiku as an “elegant” form. It is simple, earthy, and uses the oldest first principles of poetry in a way that is new to us. Therein is its charm and educational value. It is refreshing to us because it offers a poetry that is not self-involved. Change is good! Tanka is considered the more elegant poetry form (by the Japanese) but in our English hands most of the elegance has gotten rubbed off. I do think the Japanese poetry forms—haiku, tanka and renga—can be said to be more evolved simply because the Japanese keep their forms active for so many years. The tanka has been around since the time of oral traditions and is still written, contested, and enjoyed. As the tanka moves into other languages it is certainly evolving. There are moments when I believe we non-Japanese understand their poetry in the same way a cat sleeps on a book or we walk on a beach.

Whirligig: On your website you operate the Sea Shell Game in which haiku are compared as a means of finding the best of a given selection of haiku. Can you talk about your interest and involvement in the Sea Shell Game and why you continue to run this on AHA!POETRY?

Jane: The principle of the Sea Shell Game has long been a popular child’s play in Japan. To find the best in a pile of similar items, one compares them two at a time and places them into two piles—admired and not perfect. The process is repeated for each smaller pile until only one of the shells or rocks remains. Instead of simply looking at the pile and picking the best one, the person is required to consider the beauty or advantages of each individual item. Basho understood that he could use this method to educate others about poetry by comparing poems. The only book he published himself in his lifetime was a collection of comments on his comparison of a collection of hokku called The Sea Shell Game. He did write several other books but they were published by his disciples.

Whirligig: Are you then continuing or keeping alive Basho’s practice?

Jane: I guess I am. That is a lovely thought. Thank you.

Whirligig: Have you incorporated other aspects of Japanese culture into your life?

Jane: Not that I have noticed. Sometimes I feel amiss when I visit other haiku writers who are wearing kimono, having a tea garden, and Japanese art on their walls. Zen Buddhism has been important to me but my altars are more Wiccan. The more I learn about the Japanese culture, the more I realize I can only admire it— not live it. Maybe in my next life! I would like to have an African mother and a Japanese father and be born in Hawaii. I have gone there to pick out the locale. I have great hopes for my next chance to live again, but I feel I am not picking an easy life, am I?

Jane: Not that I have noticed. Sometimes I feel amiss when I visit other haiku writers who are wearing kimono, having a tea garden, and Japanese art on their walls. Zen Buddhism has been important to me but my altars are more Wiccan. The more I learn about the Japanese culture, the more I realize I can only admire it— not live it. Maybe in my next life! I would like to have an African mother and a Japanese father and be born in Hawaii. I have gone there to pick out the locale. I have great hopes for my next chance to live again, but I feel I am not picking an easy life, am I?

Whirligig: This is one of your own questions from an article you wrote for Mirrors: What makes a haiku different from other three-line short poems?

Jane: Occasionally free verse poets will simply take a line of their poetry and divide it into three short lines thinking they have then written a haiku. This rarely works because a haiku, in spite of its brevity, comes with an amazing array of rules, guidelines, and specifics. Any of these rules can be broken or ignored and the author can call the poem a haiku, but there will always be people with other rules who deem the poem not to be a haiku.

Whirligig: What do you consider your unique contribution to haiku?

Jane: In addition to thousands of haiku which I have written, I feel I have added to the understanding of how haiku work and how to write them by formulating the “Fragment and Phrase Theory” which was the first time many poets were made aware of the necessity of the two parts of a haiku. Also, from my work with Basho’s poems, I have been able to categorize certain techniques he used to make his poems “work” they do as haiku. Writers acquainted with these techniques can use them in formulating their own haiku or as guides in other forms of poetry and writing.

Whirligig: Where can we find out more about your “Fragment and Phrase Theory” and these haiku writing techniques?

Jane: The article is on the Internet and in both my haiku books by Kodansha and is also honored by being “adopted, adapted and stolen” by others. Basically it says that a haiku has two grammatical parts. One, the sentence fragment, is in the first or last line and can be shortened so it lacks an article. The second part is the phrase and consists of two of the lines. These two lines need to hold together grammatically. If they don’t the author often uses punctuation to clarify the parts. I believe a well-written haiku does not need punctuation. If the author is really skillful the reader can discover several ways of reading a haiku to get different meanings and even layers of meaning by exploring other combinations of the phrase

Whirligig: In your 2000 article for Frogpond you stated, “poetry, as it is today, is the commercialization of religious prayers, incantations, and knowledge.” What did you mean by this?

Jane: It is my belief, based on theories by others, that the earliest poetry were prayers or incantations to the gods. These ritualized sayings were remembered from one-time use to another, and as they were continued, corrections and improvements were made in the spoken prayer/incantation. These were in the oral tradition and passed from master to apprentice. At some point in every society, these sayings of love and adoration to the gods, were diverted for use in other aspects of life: the entreaty of a lover, the expression of grief, or even joy in living. An evidence of the early use of poetry is still in the Noh plays of Japan in which all the words spoken to the gods is in the form of tanka poems, no matter when the play was written and despite other dialog not being in a poetry form.

Whirligig: This makes sense and probably extends to song as well. Expand on the commercialization aspect. What are you seeing here?

Jane: I tend to see all poetry, including songs—maybe especially songs—as prayers. How often have you been humming a song fragment and when you realize what the words are, you can see what you are thinking or feeling? Or a scrap of poetry will come to mind and when you examine it, you feel a connection to someone or something that never would have occurred before? I do not see “commercialization” as a bad thing. If something is commercialized it only means it has become useful to a group of people. That is good isn’t it? I think it is delightful when our feelings of love for the divine can also focus on earthly things or people. What is there not to like here?

Whirligig: In your recent presentation at the Commonwealth Club of California you said, “Poetry is the art of piling up dissimilar images to create a new idea that has no exact name.” Can you expand on this?

Jane: Though English has more words than any other language now in use, poets still find it to be imprecise. There are no exact names for so many feelings and things. One of the poet’s jobs is finding better expressions for these by using other words. Homer’s “wine-dark seas” is an example of combining images to create a mind-picture to explain what he saw. The metaphor, saying the seas at dark look like wine, is the method of comparing the sea with wine and showing an aspect of it more exactly than saying “at dark the sea took on the colors of the sunset and turned a reddish purple.” The practiced haiku reader will see that in even Homer’s poem the implied relationship between wine / water / seas and evening as the time to have a drink of wine just when the world goes dark. The Japanese, like Homer, form their metaphors and similes directly by placing the images side by side and letting the reader find the connections. In most Western poetry the method would be to write “the sea at dark looks like a red-purple wine.”

Whirligig: You are also a visual artist working primarily in three dimensional media. You created rope sculptures while in Germany which were very successfully received. Can you talk about this work and time?

Whirligig: You are also a visual artist working primarily in three dimensional media. You created rope sculptures while in Germany which were very successfully received. Can you talk about this work and time?

Jane: In the 1960s I had a ceramic studio in Dinuba, California. I also had three children. Working in clay was too dusty and dirty to do with my small children around me, so I usually worked with clay while they were away at school. Afterwards, at home, I wove. I could work on the looms and still be there for the kids for conversation or just companionship. Wool will wait for one to return from interruptions and household chores, but clay dries out or slumps.

One Saturday in early spring, as my marriage was dissolving and my husband had brought his newest girl friend to stay the weekend in the house, I bought some rope and drove into the Sierra foothills near Squaw Valley to find an isolated tree where I could hang myself. Down a deserted ranch road I found a lovely live oak tree on a hill and began my preparation for the hanging. While looking for something to stand on before jumping off of it, I found a marvelously gray-weathered piece of wood with several holes in it. Somehow in my distracted state I got the idea of suspending that from the overhanging branch. I was so fascinated with the way it looked against the sky that I just enjoyed being with it. Slowly I forgot about wanting to end my life and finally got hungry. I drove back to the highway to a tiny rural one-stop general store. Among the groceries were great balls of twine and finger-thick ropes for ranch work. I bought one of each and took them back up to the tree.

With more rope I was able to reposition the wood piece and add a woven net around it. I worked until darkness and my fear of rattlesnakes made me go curl up in the van to sleep. The next morning the sun was shining through the weaving and I saw several more parts I wanted to add to it. I did a few more additions but also just sat and enjoyed looking at it, the company of it, and the world around my creation.

This began a pattern of my leaving the house on weekends, going up into the foothills and making weavings in the trees. When summer came I rented a cabin in Cedarbrook from the mother of a friend so the kids and I could stay close to the trees where I would do the weavings. I have no idea how many I actually did. Sometimes I would start a weaving and then, would not return to the place to finish it. Once a park ranger caught me and made me take the weaving down. I never went back to see any of them.

In Hamburg Germany, after I married Werner, I began to work with clay again and tried to re-establish my ceramic studio. The requirement for permission from the city to install a kiln was a three-year apprenticeship with a ceramic master. This was not feasible, so I tried for awhile to use other artists’ kilns but I was making far too many pots to transport them back and forth. In my distress of not being able to do clay some memory in me brought back the times of making the big weavings. Hamburg, with its several rope factories around the harbor, was the perfect place to find interesting left-over bits and pieces. Later I was able to order special ropes, or sizes, for commissioned works.

Whirligig: Did you continue to create these sculptures when you returned to the U.S.?

Jane: I tried, but here in the States we lived in a 36 x 24 foot barn so I had no inside space to work. Rope absorbs the fog and dew and rots too easily to keep it outside. The trip to San Francisco for ropes was too far and too difficult to make. Both Werner and I gave up all our sculpture work and turned our interest to writing. I had a renaissance of working in clay about nine years ago and did manage to have a studio, but only this summer did I sell off the kiln and wheel.

Whirligig: Are you currently engaged in sculptural work?

Whirligig: Are you currently engaged in sculptural work?

Jane: Yes! only now I use tiny beads. They are neat and clean, easy to lift, store, and I love the gorgeous colors. This piece is still hanging on the porch at Gualala Arts. Recently one of my sculptures was a finalist in the Fire Mountain contest. I bead several hours each day. A 17 foot tall piece will go up in October, 2009.

Whirligig: Were there elements of your childhood and upbringing which encouraged you towards the creative life?

Jane: I was an only child and my parents preferred the company of each other or other adults to mine so I was alone much of the time. Their disinterest in me gave me a freedom most kids do not have. Though it was often upsetting to find myself locked out of the house, I learned to create my own places of security and independence outdoors. I learned the value of occupying my mind with plans and ideas to avoid thinking of painful situations. I was forced into accepting any behavior of adults without question; something that got me into several situations of sexual abuse most parents would not want for their children.

Whirligig: Do you think the challenges of a difficult childhood encouraged you towards creativity—would you not have been a maker and a thinker had you had a more ideal upbringing?

Jane: I have no idea. There is a way of thinking that proposes that before birth we pick our parents and the path our lives will take this time around. This means we pick people to teach us or lead us into the lessons we need to learn. If these lessons are hard, we pick the people whom we know from other lives who love us the most because their job will be the hardest. I consider such an idea as “mind-screwing” but sometimes it is a comfort to me as it is almost unbearable to think that I was so unloved and unwanted. I am sure my need to work so much is due to the feeling of “I am dancing, do you love me yet?”

Whirligig: What is your all time favorite haiku and why?

Jane: The next one I will write. The challenge, the search, and the happiness in finding the words that will bend thoughts interests me the most. The joy on its way to me seems to be greater than the delight I have had.

flutes

echoing each other

two crows

winter solitude

the cat washes again

the tip of her tail

love songs

in the flute player's face

grief

all my years

floating in the river

a childish heart

a new language

written in my oldest books

mildew

Whirligig Interview by Nanette Wylde.

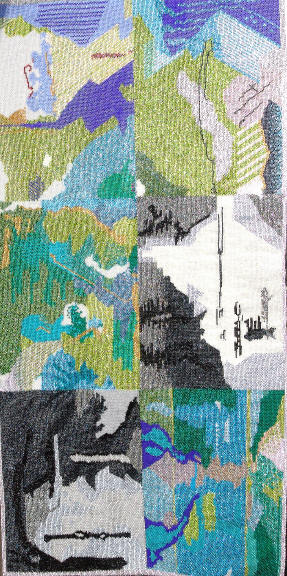

Images from the top: Haiku book River at Gualala Arts, 2009. Knot Chromatic Riff, 13′ x 18′ fiber installation. It Takes a Village, ceramics and fiber installation. Beaded Sketchbook, 30″ x 18″ recreated from sketchbook pages with 90,000 glass beads. All photos courtesy of Jane and Werner Reichhold.

Haiku by Jane Reichhold.